Characterization of β-Carboline Derivatives Reveals a High Barrier to Resistance and Potent Activity against Ring-Stage and DHA-Induced Dormant Plasmodium falciparum

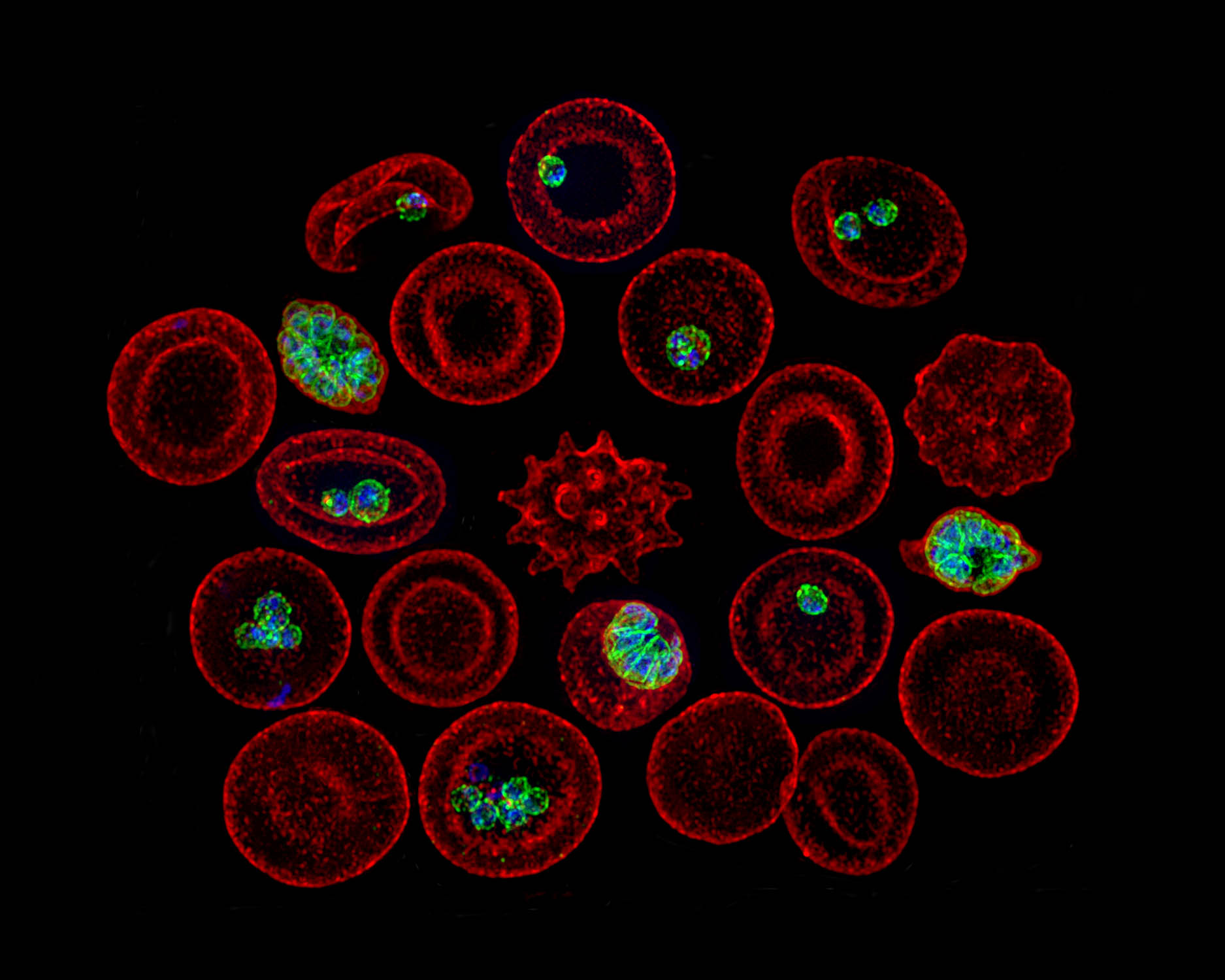

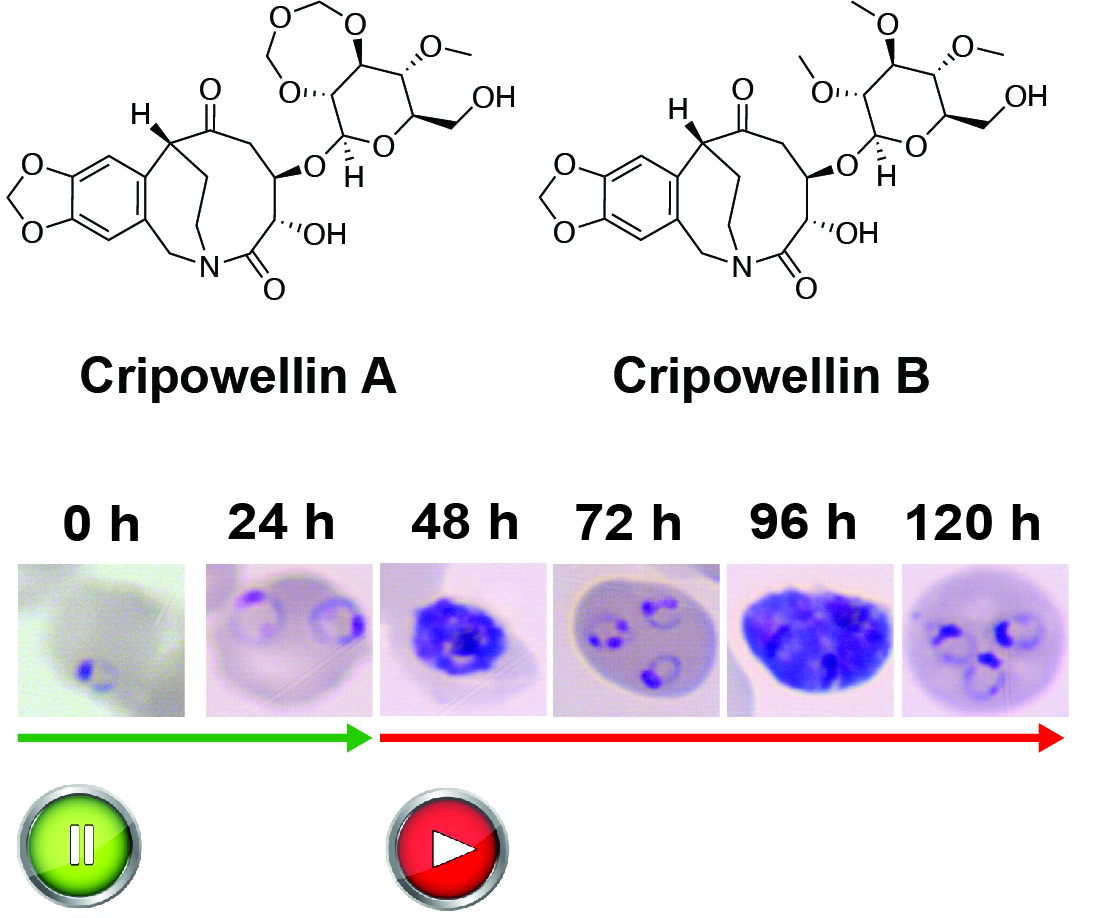

Malaria, caused by Plasmodium falciparum, remains a major global health challenge, with an estimated 263 million new infections and 597,000 deaths annually. Increasing resistance to current antimalarial drugs underscores the urgent need for new therapeutics that target novel pathways in the parasite. We previously reported a novel class of β-carboline antimalarials, exemplified by PRC1584, which demonstrated …