UGA Researcher Seeks to Unlock Secrets of Malaria Parasite

Vasant Muralidharan and his research team at the University of Georgia’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases are making great strides in understanding how the malaria parasite hijacks red blood cells to cause disease but many of the parasite’s strategies remain elusive. A new $1.875 million grant from the National Institutes of Health will allow them to continue this research.

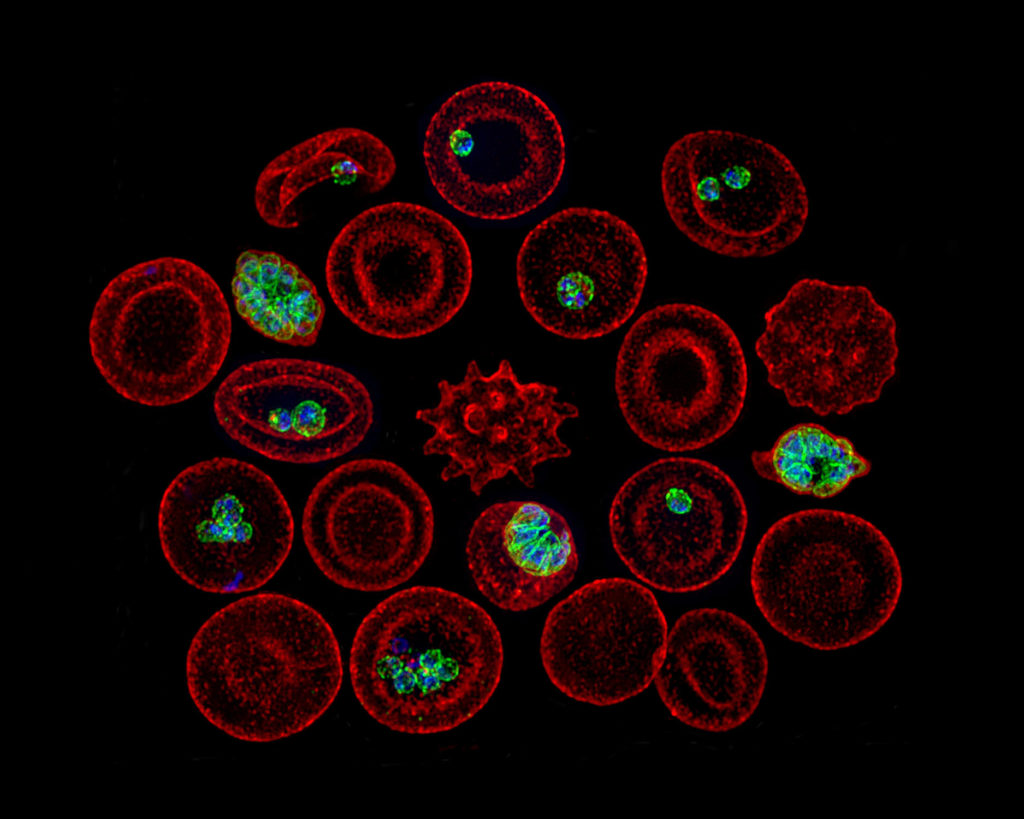

Malaria is a parasitic disease that infects nearly 220 million people and kills nearly half a million people every year. Almost all the deaths occur in young children and primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. The parasite Plasmodium falciparum invades human red blood cells which directly leads to malaria symptoms that include headaches, muscle pain, periodic fevers with shivering, severe anemia, trouble breathing, and kidney failure. The parasite can also cause the most severe forms of malaria, such as cerebral malaria which can lead to brain damage, coma and death, and placental malaria, which occurs in pregnancy and can be life-threatening to both the mother and fetus.

Complete control of the infected red blood cell is required for parasites to grow and spread. The malaria parasite remodels the host cell by exporting hundreds of parasite proteins across numerous membranes that transform all aspects of infected red blood cells to suit its needs. The export of these proteins by P. falciparum to the host red blood cells is a unique parasite-driven process that is associated with many of the clinical manifestations of malaria, including death. The mechanisms which these proteins are exported are unknown.

“Exported proteins, many of them absolutely essential for the growth of the parasite, are recognized and sorted throughout the trafficking process by dedicated machinery that we have only now begun to understand,” said Muralidharan, assistant professor in the department of cellular biology.

His lab hopes to reveal unique protein trafficking mechanisms of P. falciparum that may be targets for antimalarial drug development.

“We expect that this project will significantly advance our understanding of the protein export pathway in P. falciparum and how key decisions are made within the parasite that usher exported proteins to their site of action in the infected red blood cells,” concluded Muralidharan.

National Institutes of Health Award R01 AI130139 “Elucidating the trafficking mechanisms of effector proteins to the Plasmodium infected red blood cell.”