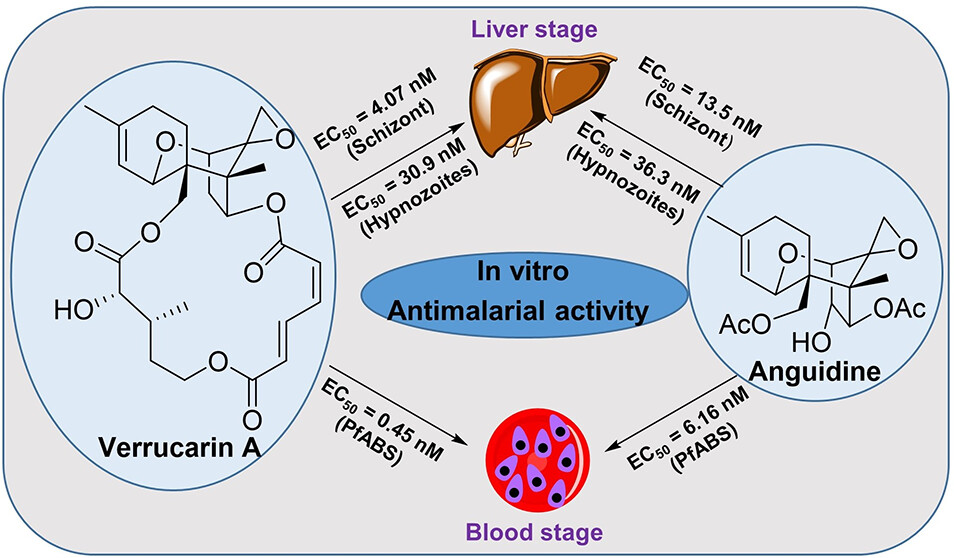

In Vitro Antimalarial Activity of Trichothecenes against Liver and Blood Stages of Plasmodium Species

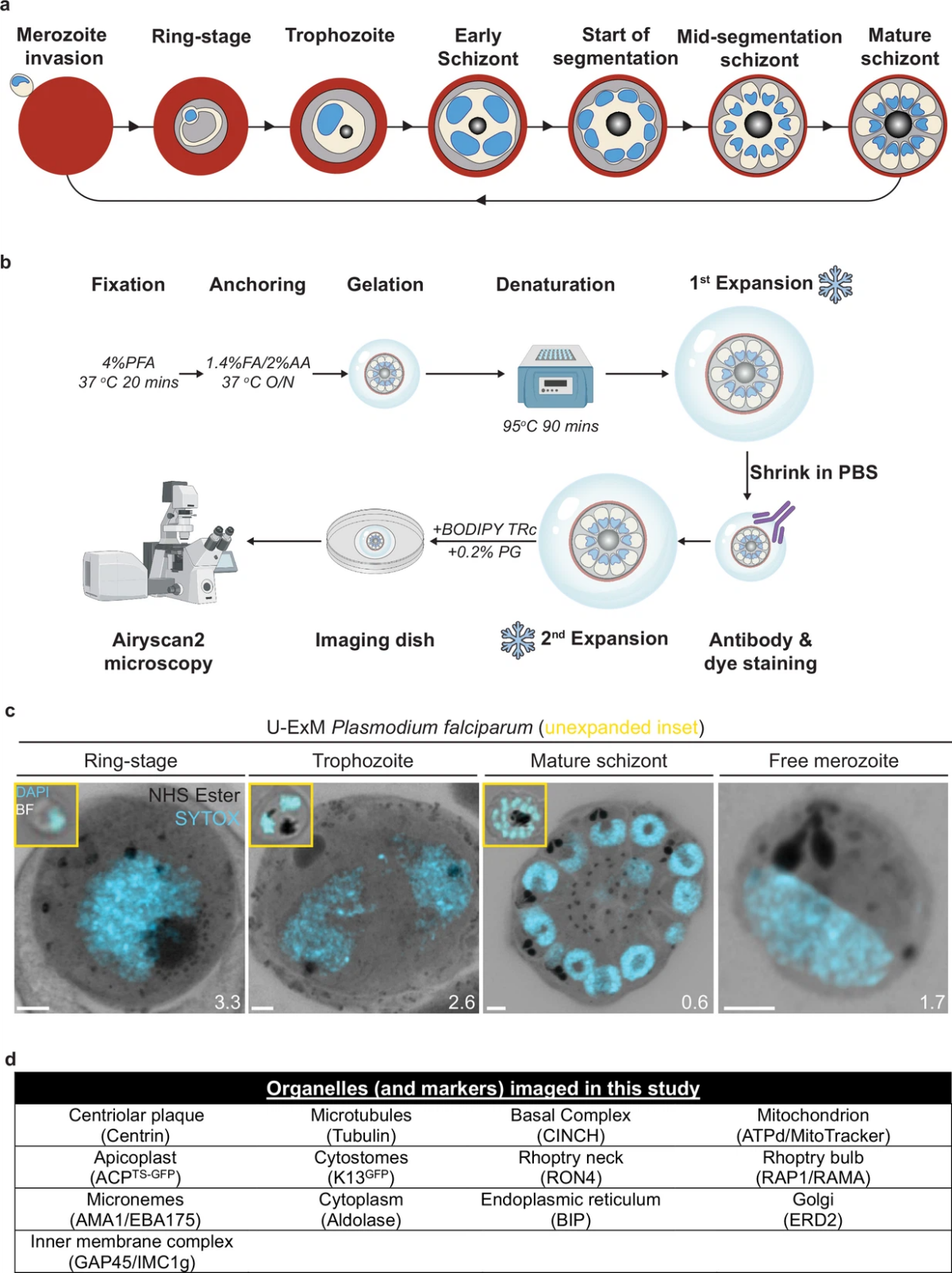

Trichothecenes (TCNs) are a large group of tricyclic sesquiterpenoid mycotoxins that have intriguing structural features and remarkable biological activities. Herein, we focused on three TCNs (anguidine, verrucarin A, and verrucarol) and their ability to target both the blood and liver stages of Plasmodium species, the parasite responsible for malaria. Anguidine and verrucarin A were found to be highly effective against the blood and liver stages of malaria, while verrucarol had no effect at the highest concentration tested. However, these compounds were also found to be cytotoxic and, thus, not selective, making them unsuitable for drug development. Nonetheless, they could be useful as chemical probes for protein synthesis inhibitors due to their direct impact on parasite synthesis processes.

Prakash T Parvatkar, Steven P Maher, Yingzhao Zhao, Caitlin A Cooper, Sagan T de Castro, Julie Péneau, Amélie Vantaux, Benoît Witkowski, Dennis E Kyle, Roman Manetsch. J Nat Prod. 2024 Jan 23. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c01019.