Chet Joyner receives $1.1 million grant to study malaria vaccine

RESEARCH WILL BE IN COLLABORATION WITH YALE UNIVERSITY

Chet Joyner, PhD, a faculty member in the Center for Vaccines and Immunology and the Center for Tropical and Emerging Diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) at the University of Georgia, is the recipient of a $1.1 million grant from Open Philanthropy to perform preclinical testing of a vaccine designed to prevent reinfection from malaria.

“A vaccine that lessens the impact of this disease will have incalculable value in terms of lives saved and the quality of life of those in the affected areas,” said Lisa K. Nolan, DVM, PhD, dean of the CVM. “We are proud of Dr. Joyner’s work and that he has chosen to do it in the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Georgia.”

Joyner is collaborating with Dr. Richard Bucala, MD, PhD, of Yale University to test the vaccine that targets Plasmodium-encoded Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (pMIF), a protein secreted by Plasmodium falciparum, a pathogen that causes malaria.

The science team for Open Philanthropy, which recommended grants to Joyner and Bucala for the three-year study, believes that vaccinating against pMIF may provide an important boost to the efficacy of existing malaria vaccines, according to a statement on its website, openphilanthropy.org.

Open Philanthropy is a Silicon Valley-based nonprofit which aims to use its resources to help others as much as possible. They fund work in many areas, including global health.

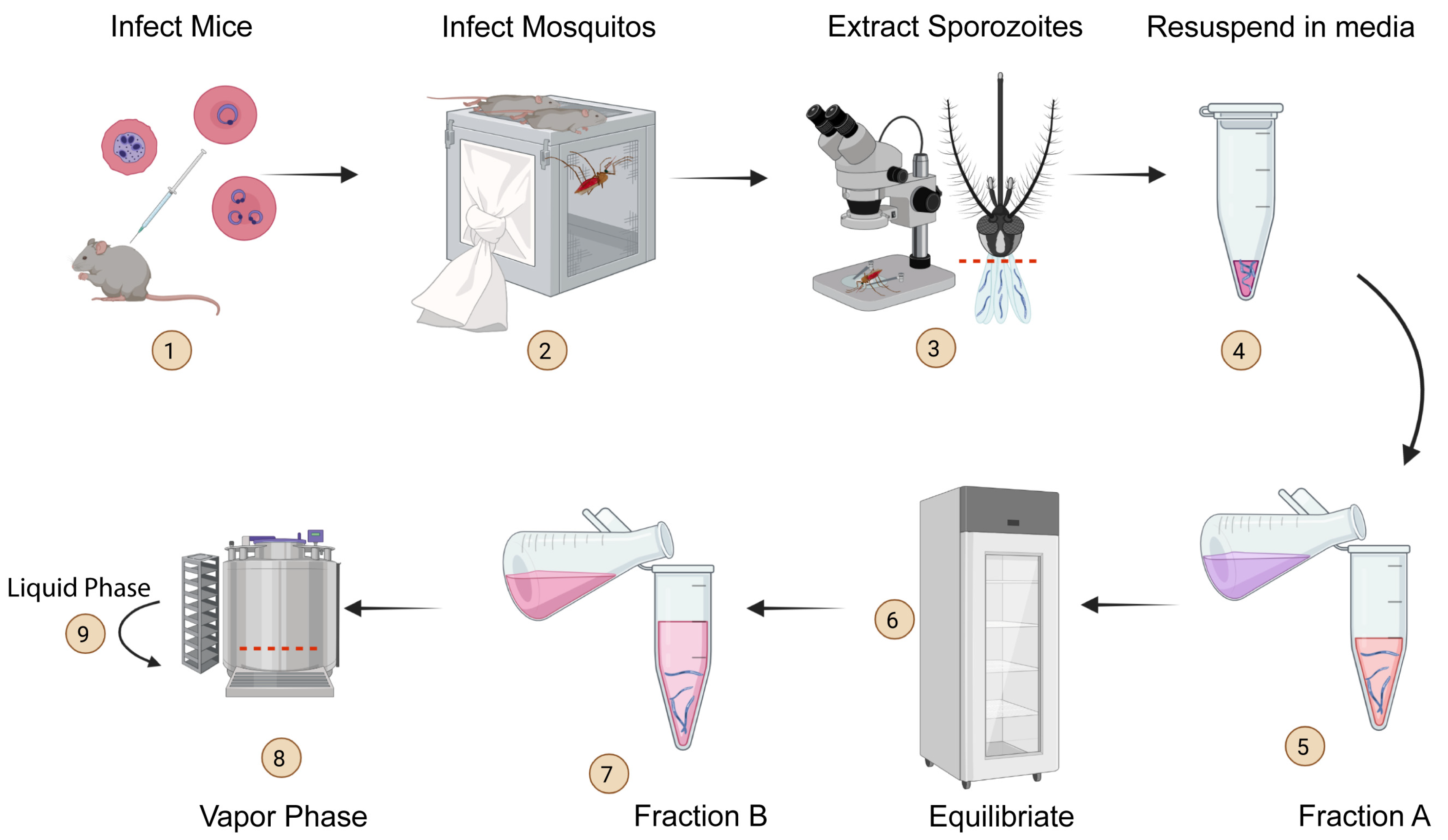

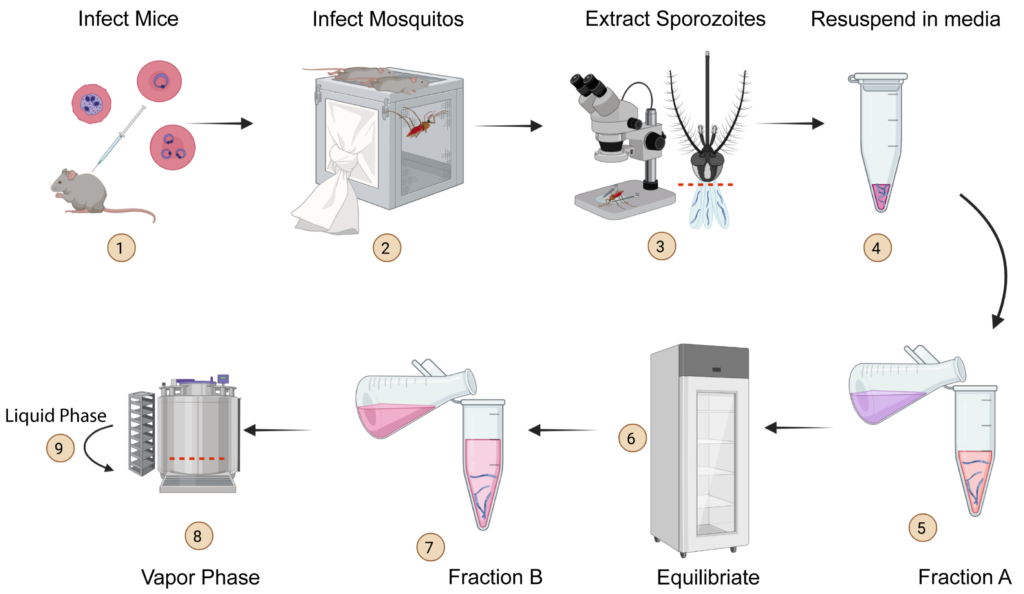

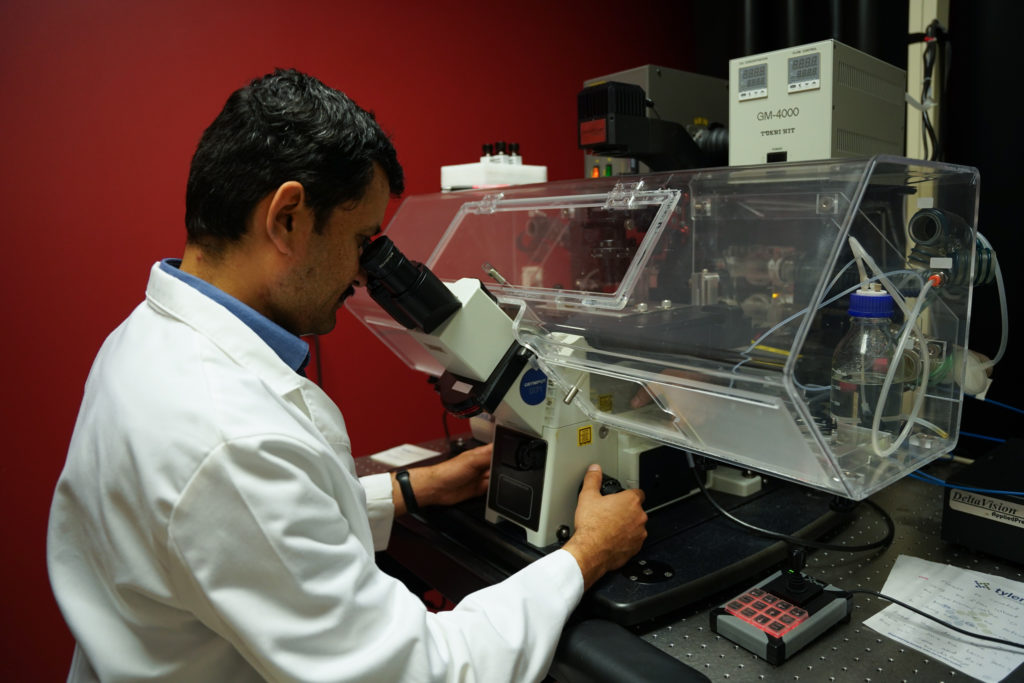

Joyner, who was recruited from Emory University to join the CVM in January of 2020, said the college is uniquely positioned to test the efficacy of the vaccine developed by Bucala at Yale.

“We are a strong malaria group with unique infrastructure and facilities that can support this necessary research within the CVM,” Joyner said.

Immunity to malaria is acquired naturally after exposure, but the disease can be fatal to children younger than five and debilitating up to age 10 because malaria parasites disrupt the immune system’s response with their own proteins that mimic the human Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF).

Not only does the resulting illness cause children to miss school, but it also leads to long-term cognitive decline due to nutritional deficiencies. Parents miss work to care for children and the economic impacts compound.

According to the World Health Organization’s 2022 World Malaria report, an estimated 247 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide in 2021 and 619,000 people died, mostly children under the age of five in sub-Saharan Africa.