CTEGD at ASTMH Annual Meeting

Many of CTEGD researchers and collaborators will be at the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene’s Annual meeting in Baltimore, MD next week. Below is a list of presentations where you can hear about the work we are doing.

November 5

Session Parasitology (ACMCIP) Pre-Meeting Course: Single Cell Biology for Parasitologists – 2:00 – 2:45 pm, Hilton Holiday Ballroom 4 (East Building, 2nd Floor)

Bioinformatics Approaches to Single Cell Parasitology

Presenter: Jessica Kissinger

November 6

Session 24 – Protozoa – 10:30 – 10:45 am, Convention Center Room 337/338

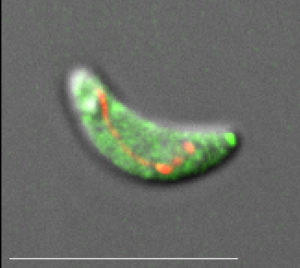

84 – A natural mouse model for cryptosporidiosis

Presenter: Adam Sateriale (Striepen Research Group)

Session 15 – What Kinds of Molecules are Needed to Control and Eradicate Malaria? – 10:55 – 11:15 am, Convention Center Ballroom I (Level 400)

TCP3: Strategies for identifying novel anti-relapse agents

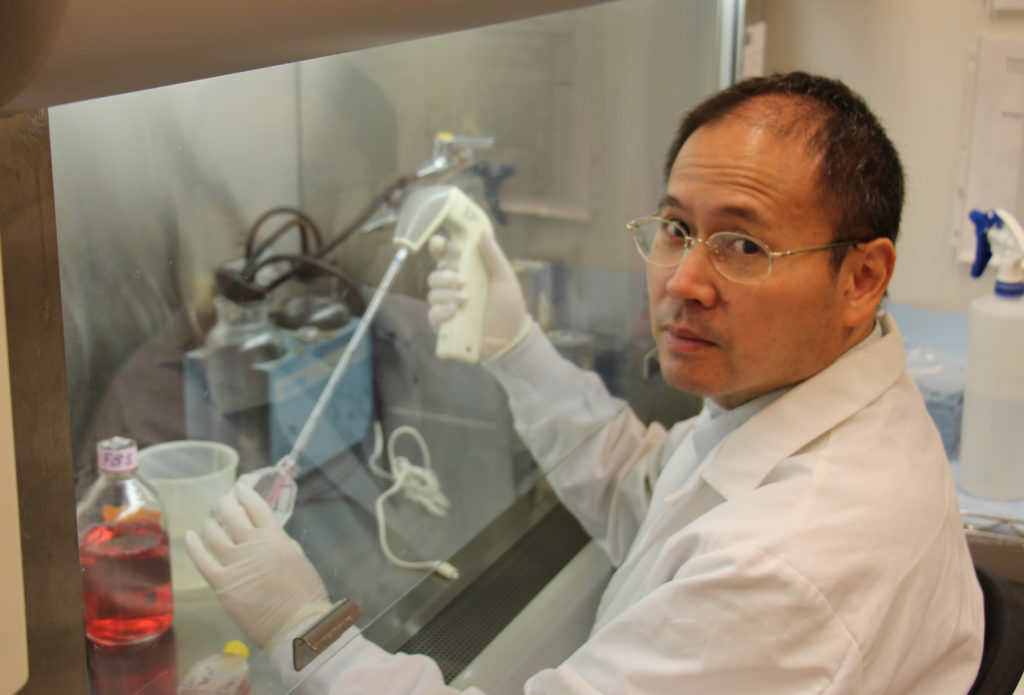

Presenter: Dennis Kyle, director of CTEGD

Session 28 – Poster Session A – 12:00 – 1:45 pm, Convention Center – Hall F and G (level 100)

LB-5052 – Drug Resistant Phenotypes for Artemisinins in GFP Expression Plasmodium falciparum From SE Asia

Presenter: Vivian Padin-Irizarry (Kyle Research Group)

LB-5033 – PfGRP170 is an essential ER protein in the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum

Presenter: Heather Bishop (Muralidharan Research Group)

November 7

Session 84 – Kinetoplastida: Molecular Biology and Immunology – 10:15 – 10:30 am, Convention Center Room 341/342

768 – Alterations in the IL27 pathway are correlated with the loss of Trypanosoma cruiz-specific T cells in patients with chronic Chagas Disease

Presenter: Maria Natale (collaborator, Tarleton Research Group)

Session 86 – Poster Session B – 12:00 -1:45 pm Convention Center – Hall F and G (level 100)

LB5207 – Investigating the role of PfHsp70x, the sole parasite exported Hsp70, in the display of antigens on the surface of the P. falciparum infected RBC

Presenter: David Cobb (Muralidharan Research Group)

877 – Resolving Temperature-driven Malaria Transmission Models

Presenter: Kerri Miazgowicz (Murdock Research Group)

1039 – EuPathDB: Powerful Data-Mining Tools for Exploring the Biology of Host-Pathogen Interactions

Presenter: Susanne Warrenfeltz (Kissinger Research Group)

Session 106 – Science is Real: Climate Change Impacts on Vector Borne-Diseases – 4:20 – 4:40 pm, Convention Center Ballroom IV (level 400)

Estimating vector-borne disease transmission in a variable environment

Presenter: Courtney Murdock

November 8

Session 145 – Poster Session C – 12:00 – 1:45 pm, Convention Center, Hall F and G (level 100)

LB-5362 – Global metabolic profiles differentiate acute and chronic malaria in rhesus macaques and humans

Presenter: Regina Joice Cordy (collaborator, Kissinger Research Group)

1672 – Multi-omic analysis of severity of infection in Macaca mulatta infected with Plasmodium cynomolgi

Presenter: Juan Gutierrez (collaborator, Kissinger Research Group)

LB-5397 – Enhancement of three closely-related species of Cryptosporidium genome annotation resources

Presenter: Rodrigo Baptista (Kissinger Research Group)

November 9

Session 192 – ACMCIP: Malaria and Protozoal Diseases – Biology and Pahtogenesis – 11:15 – 11:30 am, Convention Center Room 321/322/323 (level 300)

2013 – A natural mouse model for cryptosporidiosis

Presenter: Adam Sateriale (Striepen Research Group)

Session 188 – Malaria: Application of Innovative Technologies – 11:30 – 11:45 am, Convention Center Ballroom II (level 400)

1987 – Characterization of physiological signatures of Plasmodium infections in nonhuman primates using a continuous telemetry system

Presenter: Jessica Brady (collaborator, Kissinger Research Group)

Being able to create these synthetic molecules is a necessary step in the drug discovery process. Natural material can be costly to collect or not available in abundance. While the southern magnolia seems to be abundant in the yards of Georgia, its natural range only stretches from coastal North Carolina south to central Florida, and then west to eastern Texas and Oklahoma. In addition, due to environmental differences, many times compounds isolated from a plant from one part of the world cannot be found in the same plant grown in another which reinforces the need to focus on active compounds that can be resynthesized in the lab.

Being able to create these synthetic molecules is a necessary step in the drug discovery process. Natural material can be costly to collect or not available in abundance. While the southern magnolia seems to be abundant in the yards of Georgia, its natural range only stretches from coastal North Carolina south to central Florida, and then west to eastern Texas and Oklahoma. In addition, due to environmental differences, many times compounds isolated from a plant from one part of the world cannot be found in the same plant grown in another which reinforces the need to focus on active compounds that can be resynthesized in the lab.

Mosquitoes provide an interesting system for addressing these issues because almost all species must feed on blood from a vertebrate host, such as humans or another animal, to reproduce. However, blood feeding exposes mosquitoes to microorganisms that cause disease in mosquitoes, the vertebrate hosts mosquitoes feed upon, or both. Background studies by Strand and Brown have shown that certain hormones co-regulate reproduction and immune defense.

Mosquitoes provide an interesting system for addressing these issues because almost all species must feed on blood from a vertebrate host, such as humans or another animal, to reproduce. However, blood feeding exposes mosquitoes to microorganisms that cause disease in mosquitoes, the vertebrate hosts mosquitoes feed upon, or both. Background studies by Strand and Brown have shown that certain hormones co-regulate reproduction and immune defense.