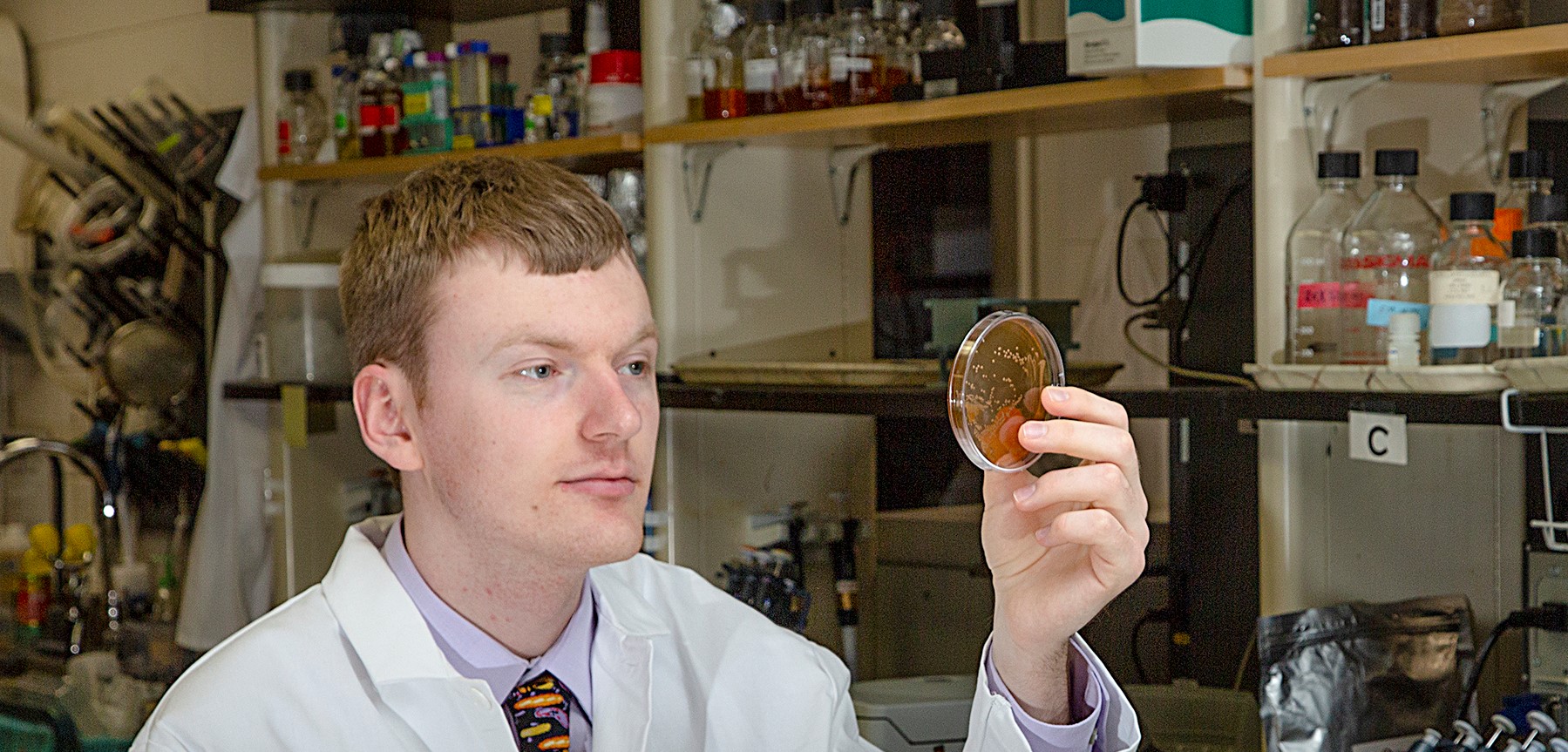

PhD Candidate Ale Villegas and Advisor Dr. Vasant Muralidharan (Photo Courtesy of Vasant Muralidharan)

Malaria’s connection to Georgia goes back to the colonial period. The Southeastern United States provided prime conditions for a thriving mosquito population which ensured the spread of the disease. The state capital moved from Louisville to Milledgeville in 1806 in part because of malaria outbreaks among the state’s General Assembly.

Later, the federal Office of Malaria Control in War Areas was established in Atlanta instead of Washington D.C. because of its proximity to malaria. The center was succeeded in 1946 by the Communicable Disease Center which is now the Centers for Disease Control. While Malaria was mostly eliminated in the U.S. by 1951, it still impacts millions of people around the globe. Cue Ale Villegas, a doctoral candidate in Cellular Biology.

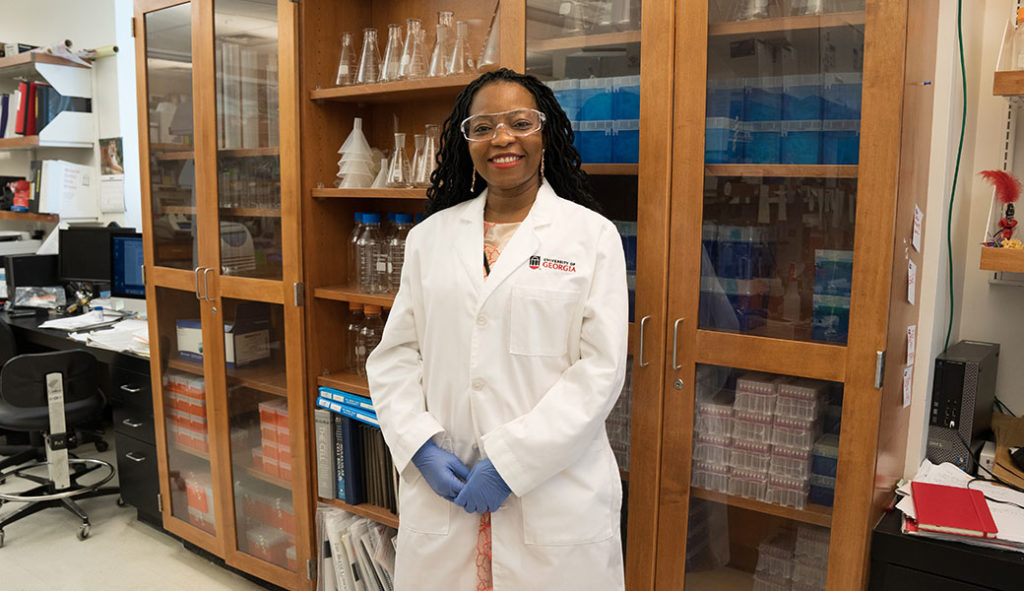

Villegas and her advisor, Dr. Vasant Muralidharan, were recently awarded a Gilliam Graduate Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The goal of the fellowship is to increase the diversity among scientists who are prepared to assume leadership roles in science. The program selects pairs of students and their dissertation advisers based on their scientific leadership and commitment to advance diversity and inclusion in the sciences.

Villegas’s research is on the edge of the unknown. She works with Muralidharan in UGA’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases where they aim to understand the parasite that causes malaria.

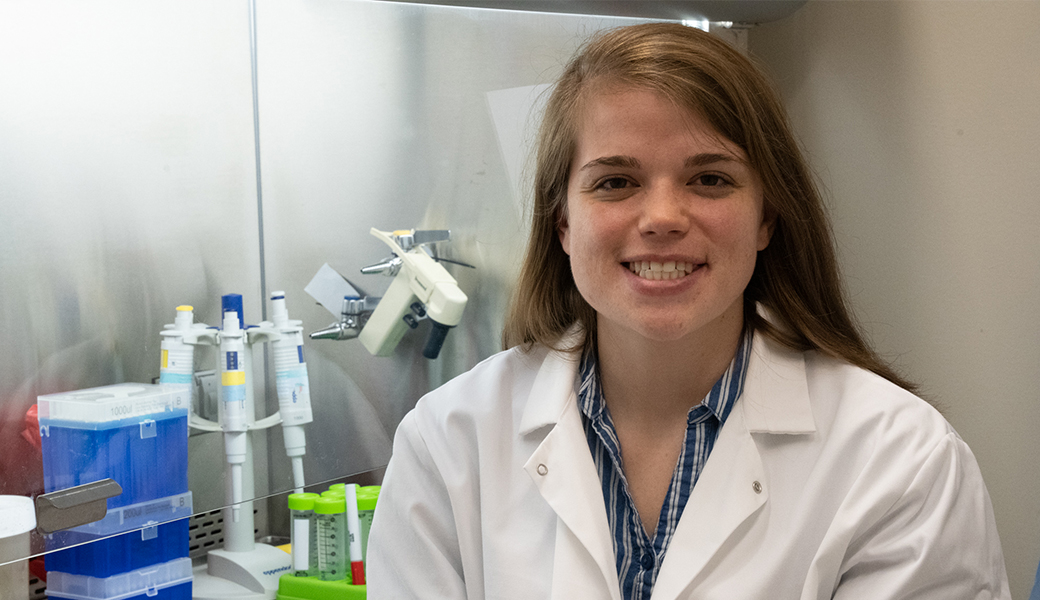

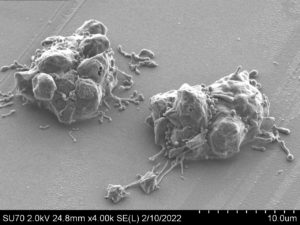

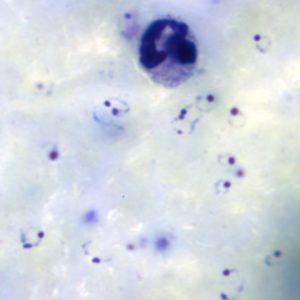

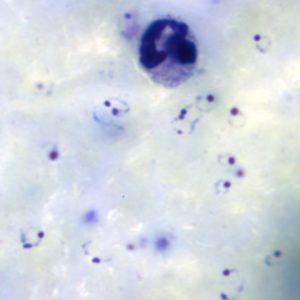

“I’m exploring the mechanisms by which malaria parasites develop in human red blood cells,” said Villegas. “I am studying Plasmodium falciparum, the most common and deadly species that infects humans. These studies can inform therapeutic treatments in the future.”

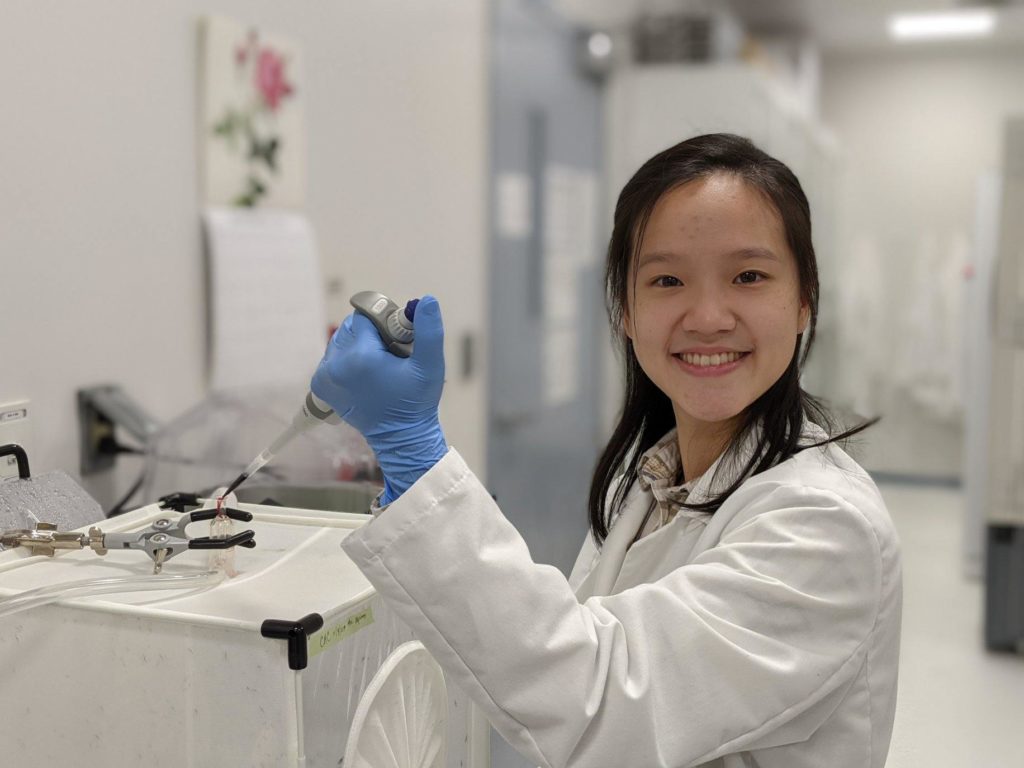

PhD Candidate Ale Villegas. Villegas is in the cellular biology department. (Photo Courtesy of Ale Villegas)

Villegas specifically studies a malaria parasite glycosyltransferase or an enzyme that adds sugar molecules to other biomolecules. These enzymes may be needed by the parasite to survive and resist the immune response. There are few experts or studies in this area, but Villegas saw beyond those challenges to the critical importance of understanding malaria immune response.

“She is a very talented young scientist who has undertaken a challenging and high-impact research project,” said Muralidharan. “Her initial work was fraught with technical difficulties and setbacks, most of which are attributable to the difficulties in working with the hard-to-study malaria parasite. I am very impressed by her toughness and intellectual capacity as she solved one technical issue after another. She is now poised to move the field forward in a meaningful way.”

Villegas has also worked with Dr. Robert Haltiwanger and his graduate students in the Complex-Carbohydrate Research Center at UGA to advance her research. Haltiwanger is a leading expert on fringe-like glycosyltransferases like the enzyme she studies.

“Having Dr. Haltiwanger on campus is amazingly lucky,” said Villegas. “He and his graduate students go above and beyond when I need help or need to try out experiments. I’m glad to have access to his knowledge, experienced grad students, and sometimes his reagents!”

“What these parasite-derived sugar modifications are and how they form could inform a better vaccine or other drug therapies for malaria,” said Villegas.

Rings of P. falciparum in a thick blood smear. (Photo Courtesy of CDC)

Malaria still kills around 450,000 people each year. Most of these victims are children under the age of five. There are no effective vaccines and the parasite has gained resistance to all antimalarials currently in clinical use. Villegas’ research on this parasite sugar-adding enzyme could have important implications for future treatments and vaccine development.

The Gilliam Fellowship allows Villegas to pursue other passions in addition to science. She is a leader in student advocacy and devoted to helping students gain access to resources to advocate for themselves.

“I practice and promote student and self-advocacy by serving on the UGA Graduate Student Association and the student science policy group (SPEAR),” said Villegas. “With fellow SPEAR members, I have organized advocacy days workshops to empower students to advocate for themselves and issues they are passionate about.”

“I have found that those who are most successful understand failure very well,” said Muralidharan. “We need to normalize this. We are working to figure out the unknown. Failure in science is normal, and it is critical for discovery.”

Dr. Vasant Muralidharan’s lab utilizes molecular genetics, cell biology, and biochemistry to study the biological mechanisms driving the disease.

The award also provides funding for Muralidharan to develop mentoring skills and to share those skills with other faculty members at UGA. He has served as a mentor for many either first-generation or underrepresented students in STEM. He explains that scientists need strong support systems, especially when they experience failure in the lab. The people around them help the most.

When Villegas graduates, she hopes to continue working on and learning about science policy and advocacy. Her ideal job would allow her to be a scientist in addition to being an advocate for graduate students and a creator of equitable graduate education policies.

The Gilliam Graduate Fellowship provides Villegas an opportunity to move closer to her goals and to contribute to potentially life-saving research that could reduce the global threat of malaria.

Announcement from Howard Hughes Medical Institute

This story originally appeared at UGA’s Graduate School.