July 2025 Newsletter

Click on the image above to see the picture gallery with captions.

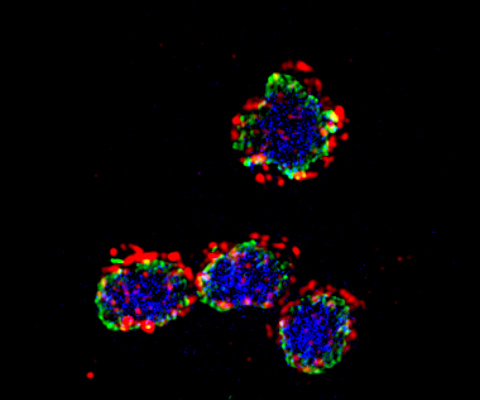

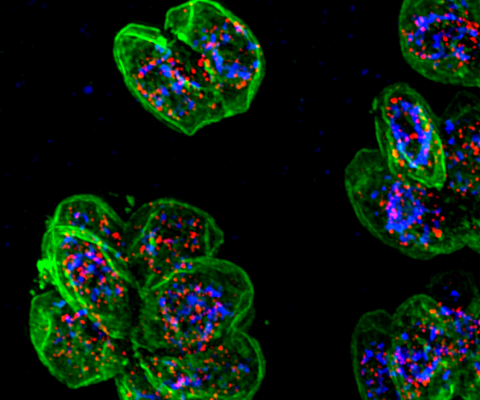

UGA biochemists create new tool to study biological process in parasites

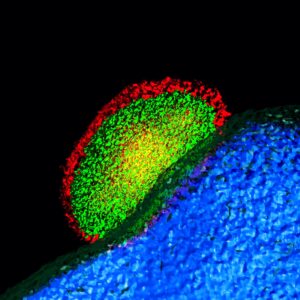

Researchers in the West Laboratory are interested in how unicellular parasites thrive in their environments. Focusing on post-translational modifications of proteins, particularly a crucial process called glycosylation, researchers are gaining insights into how this basic life process in parasites can lead to better treatments for diseases. Read more.

CTEGD faculty member Jessica Kissinger earned the distinction of University Professor, a title bestowed on those who have made a significant impact on the university in addition to fulfilling their regular academic responsibilities. Read more

Diagnosing Chagas is complicated — in both people and canines. False negatives aren’t unheard of, leading people to not know they or their pets are infected. And that delays treatment. Read more.

Researchers at the University of Georgia’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases have developed the first test to determine whether treatment for Chagas disease was effective. Read more.

Chester Joyner, assistant professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s infectious diseases department and member of CTEGD, is integrating molecular biology, immunology and vaccine development to develop new therapies needed to treat and prevent malaria. Read more.

Every year, malaria evades the immune defenses of nearly 250 million people. But Samarchith “Sam” Kurup is determined to outsmart the parasite before it strikes. Read more.

Support our mission with a financial gift TODAY! Support CTEGD.

Alumni News

Lilach Sheiner received the prestigious C.A. Wright Medal.

Hilary Danz took a new position at Sanofi. She is now the mRNA Center of Excellence New Vaccine Research Lead.

Mattie Pawlowic was awarded a Career Development Award from Wellcome Trust in March.

Justin Widener has left Boehringer Ingelheim and is now at Elano Animal Health.

Nuria Negrao was interviewed by the Northern California Chapter of the American Medical Writers Association.

Vivian Padin-Irizarry has been promoted to Associate Professor of Biology with tenure at Clayton State University.

Nathan Chasen has recently accepted an Assistant Professor position at the University of South Alabama.

Alona Botnar is now the Associate Director of International Market Access – Oncology Pipeline at AbbVie.

Hyun Woo (John) Kim started a new position at Helix Biostructures.

Trainee News

Clyde Schmidt (Kurup Lab) won the award for Outstanding Talk for his talk “Type-I IFNs induce GBPs and lysosomal defense in hepatocytes to control malaria” at the American Association of Immunologists annual meeting.

Alex Garrot (Kurup Lab) received a 3rd place poster award at the Woods Hole Immunoparasitology meeting.

CTEGD members in the news

Rick Tarleton:

Researchers secure funding to advance Chagas disease research (News-Medical.net)

Investigators are studying Chagas disease with a One Health approach (DVM360)

UGA and Texas A&M Researchers tackle Chagas disease in dogs and humans (WUGA)

Countable Labs Launches Single-Molecule DNA Counting System, PCR Application (GenomeWeb)

UGA Pioneers First Test for Chagas Disease Cure (Mirage)

UGA researchers develop first test of cure for Chagas disease (Newswise)

¿Se curó la infección de Chagas? Un nuevo test podría dar la respuesta (Infobae)

Chagas disease: Test for cure (Outbreak News Today)

AN2 Therapeutics and DNDi Collaborate on Clinical Development of Promising New Oral Compound to Treat Chronic Chagas Disease (Yahoo! Finance)

Brooke White:

Researchers Warn Chagas Disease-Carrying Insects Have a “Secure Foothold in the U.S.” (Best Life)

Dennis Kyle:

Brain-eating amoebas are rare. But hot weather increases the risk (Washington Post)

Brain-eating amoeba: Who is most often infected? (Rochester First) (CBS42) (The Hill)

Podcasts featuring CTEGD members

Recently published research

The Tarleton Research Group discusses the importance of persistence and dormancy in Trypanosoma cruzi infection and Chagas disease in a review published in Current Opinion in Microbiology.

Read more of the recently published research from all our labs.

Read more of the recently published research from all our labs.

Newly funded projects

Chet Joyner received an award from Abbott Laboratories for the production of Plasmodium isolates. He also received an award from the National Institutes of Health to establish P. vivax lines that grow in optimized culture conditions to develop a continuous, high yield culture system for P. vivax to support mechanistic studies that will lead to new therapies. A grant from Good Ventures Foundation will fund preclinical evaluation of safety, immunogenicity and protective efficacy against P. falciparum challenge of a nanoparticle vaccine encoding a Plasmodium MIF ortholog in Aotus nancymaae. Medcicnes for Malaria Venture has funded Joyner’s project for SERCAP testing for MMV2682.

Rick Tarleton received an award from the National Institutes of Health. The goal of this project is to complete adaptation of the rapid and inexpensive T. cruzi UltraPCR method for highsensitivity detection of T. cruzi, validate its use for confirming infection and monitoring treatment impact, and provide the justification for ultimately deploying this assay for human and veterinary diagnostic use. With his collaborators at Texas A&M University, he also received a US Department of Homeland Security grant for a Canine Chagas Disease Prevalence, Prevention, and Operational Capability Protection Study.

Vasant Muralidharan, with collaborators at the University of California – Riverside, received a grant from the National Institutes of Health for Decoding the Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Gene Regulation.

Sam Kurup received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the mechanisms of human immune response to Plasmodium infection in the liver.

Chris West, in collaboration with colleagues at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, received two grants from the National Institutes of Health. One to study protist oxygen sensing in human disease and the other is to study the organization and function of the Toxoplasma daughter cell scaffold.