All the pieces matter: UGA researchers collaborate to solve malaria puzzle

They say what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Whoever coined that adage had probably never heard of Plasmodium.

It’s a microscopic parasite, invisible to the naked eye but common in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world. Each year, millions of people are infected by Plasmodium and exposed to an even more debilitating—and often deadly—disease: malaria.

Malaria is one of the deadliest diseases known to man. It can lead to extreme illness, marked by fever, chills, headaches and fatigue. More than half the world’s population is at risk of contracting the disease, and those who develop relapsing infections suffer a host of associated costs.

Limited educational opportunities and wage loss lead to an often unbreakable cycle of poverty. Vulnerable populations are most at risk.

“When I’m teaching in an endemic area like Africa, it isn’t unusual to find a student who needs to sleep during part of the workshop because they have malaria,” researcher Jessica Kissinger said.

It’s a challenge she and her collaborators in the University of Georgia’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases (CTEGD) are trying to combat.

When the Center was established in 1998, there were only a couple of faculty members studying Plasmodium. Now, 25 years later, it has become a world-class powerhouse of multidisciplinary malaria research. Scientists examine various species of the dangerous parasite, studying its life cycle and the mosquito that transmits it.

While Plasmodium seems to have superpowers that allow it to evade detection and resist treatment, CTEGD researchers are working together to innovate and transfer science from the lab to interventions on the ground.

A 50,000-piece puzzle with no edges

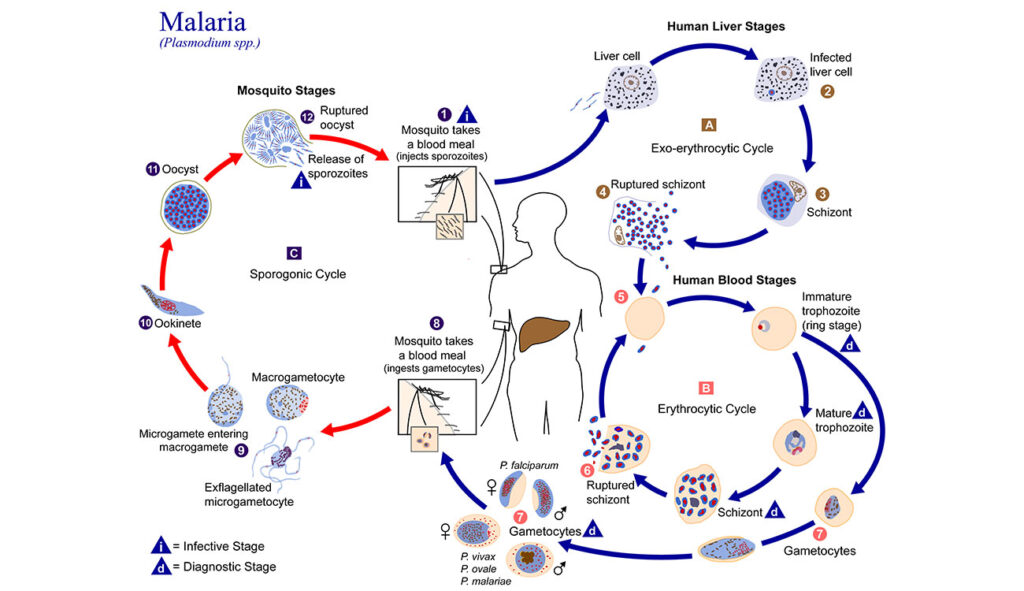

Plasmodium is a complex organism, and studying it is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. Some researchers contribute pieces related to the blood or liver stages of the parasite’s lifecycle, while others provide insights about hosts interactions. One way UGA’s research connects with the global effort to eradicate malaria is PlasmoDb—a resource derived in part from Kissinger’s research that is now part of a host of databases under the umbrella of The Eukaryotic Pathogen, Vector and Host information Resource (VEuPathDB).

“Our group has been able to help many others when their research question crosses into an –omic,” Kissinger said, referring to in-house shorthand for domains like genomics, proteomics and metabolomics.

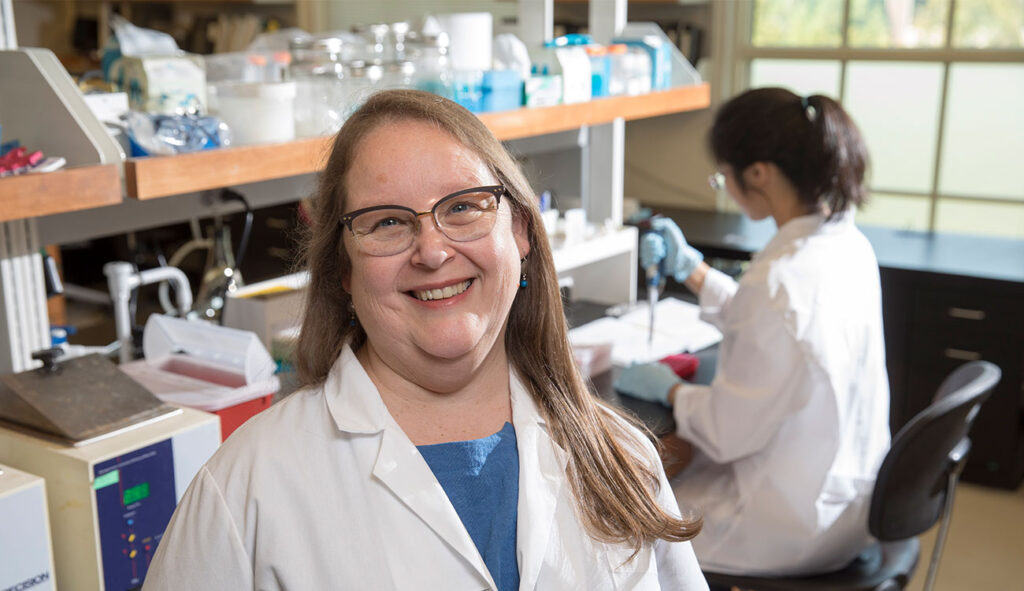

Kissinger, Distinguished Research Professor of genetics in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences, became interested in malaria and Plasmodium during her postdoctoral training at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Working from an evolutionary biology perspective, she’s interested in how the parasite has changed over time.

“I see it as an arms race,” Kissinger said. “I want to understand what moves they have and can make.”

To understand the parasite, you must dive deep into its genetic code.

Kissinger paired her work in Plasmodium genomics with her interest in computing by helping create the database with information from the Plasmodium genome project completed in 2002. The Malaria Host-Pathogen Interaction Center, one of her projects at UGA, was a seven-year, multi-institutional effort funded, in part, by NIH to create data sets that could be used in systems biology of the host-pathogen interaction during the development of disease.

“Wouldn’t it be neat if, from the beginning of infection all the way to cure, you knew everything that was going on in the organism all the time?” Kissinger said, noting the project’s goal.

They generated terabytes of data that, along with data from the global research community, are publicly accessible and reusable through PlasmoDB and other resources.

Being part of a group that is studying so many different aspects of malaria helps put Kissinger’s research into perspective. Now, in addition to understanding the parasite, she also thinks about tools needed to facilitate research from peers.

High-tech solutions rely on basic research

David Peterson, professor of infectious diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine, noted that low-tech solutions have mitigated malaria’s human costs. He acknowledged, however, that their long-term goals required more.

“We have to acknowledge that low-tech solutions, such as mosquito nets, have saved lives,” Peterson said. “But to develop the high-tech solutions that will one day end malaria, we need basic research.”

Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to malaria because their existing immunity to malaria fails to protect them during pregnancy. Placental malaria often results in premature birth and low birth weight.

Peterson is interested in a binding protein that allows the parasite to adhere to the placenta. While many P. falciparum parasites have only one gene copy that encodes the placental binding protein, Peterson is investigating Plasmodiumisolates with two or more slightly different copies.

But why isn’t one copy enough?

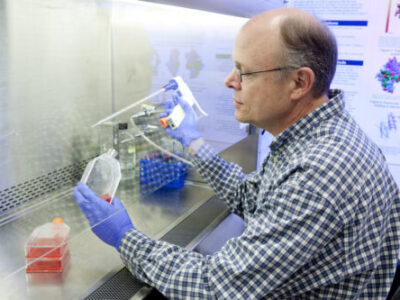

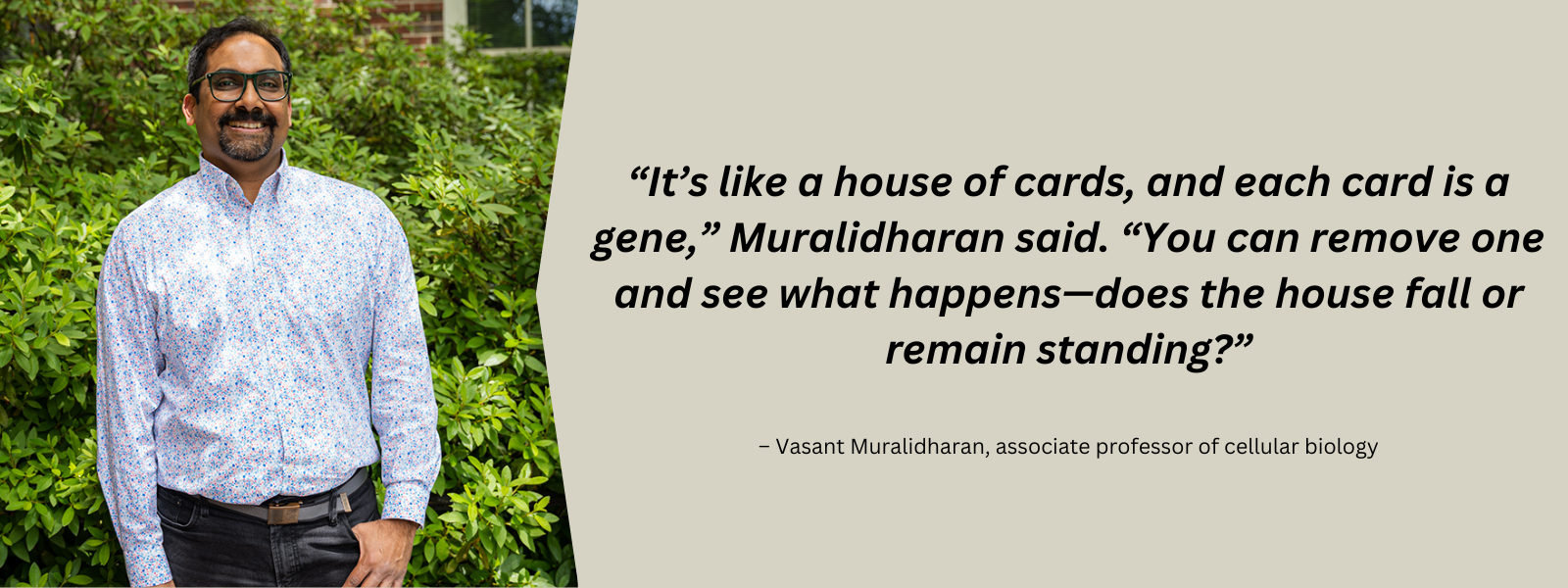

That is the primary question Peterson is focused on. He wants to understand how Plasmodium uses extra copies to evade the immune system, distinguishing the role of each requires tools that Vasant Muralidharan, associate professor of cellular biology, has.

Muralidharan’s interest began when he contracted malaria himself. Through access to good health care, he made a full recovery, but the pain he endured remained. He wanted to understand this parasite. Even more, he wanted to make an impact with research.

His graduate training focused on biophysics, but soon his interest in Plasmodium resurfaced. He discovered there was a lack of tools to study the parasite on a genetic level.

“It’s like a house of cards, and each card is a gene,” Muralidharan said. “You can remove one and see what happens—does the house fall or remain standing?”

In the days before CRISPR/Cas9, there wasn’t a precise way to remove genes. Muralidharan is among the pioneers of gene-editing techniques in Plasmodium.

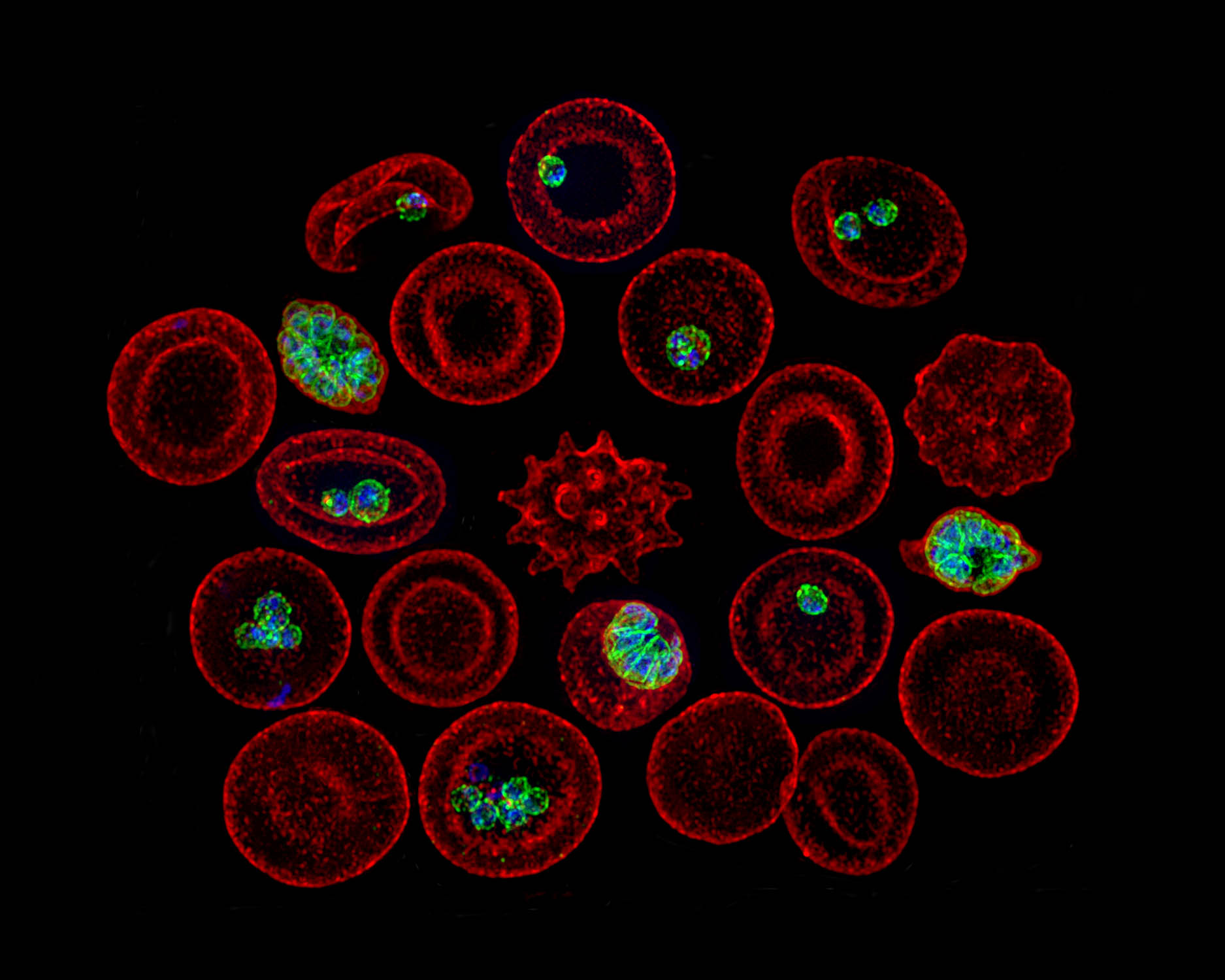

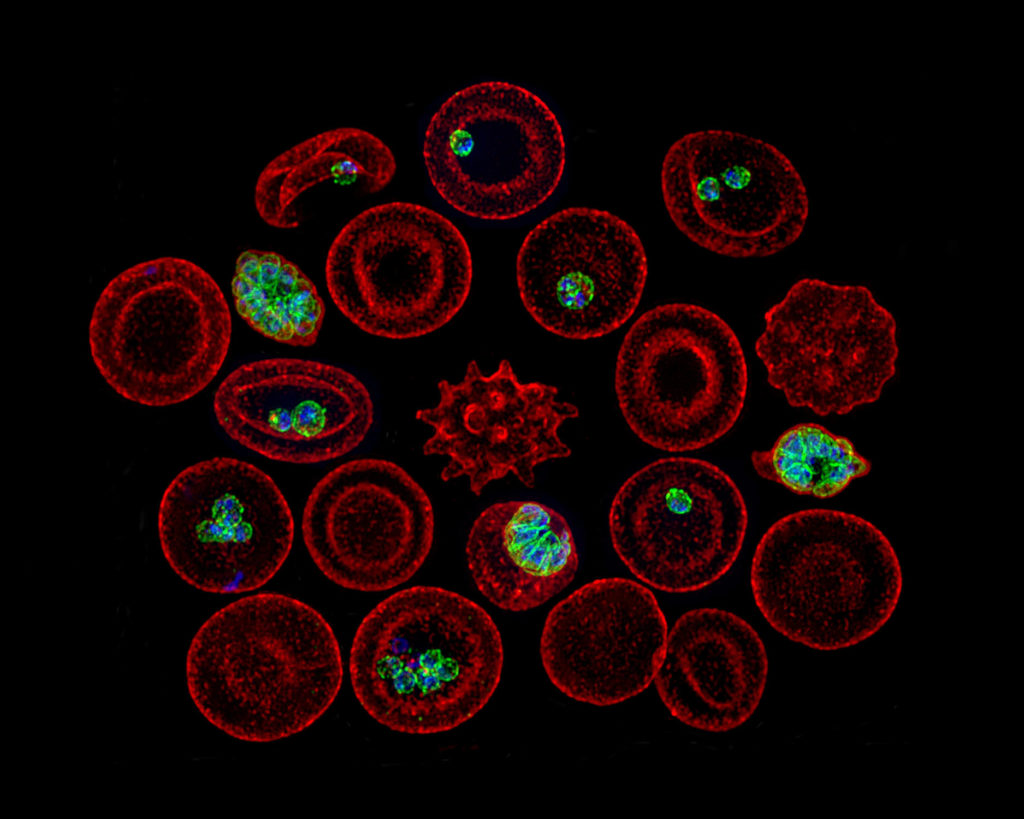

Like Peterson, Muralidharan focuses on proteins secreted by the parasite. He studies the largely unknown process that allows the parasite to invade a red blood cell (RBC), replicate and escape. The lack of tools was a major hindrance, so Muralidharan created new ones.

These tools have been used by Muralidharan’s CTEGD and CDC colleagues to see how drugs might fail. Muralidharan’s laboratory can create mutant Plasmodium parasites that become resistant to a particular drug, and genome sequence databases allow researchers to check if that mutant is already circulating in malaria endemic regions.

Building a research bridge to endemic regions

Plasmodium vivax is the predominant malaria parasite in Southeast Asia. It causes “relapsing malaria” during which some parasites go “dormant” after entering the liver instead of reproducing. This phase is a major obstacle for current treatments.

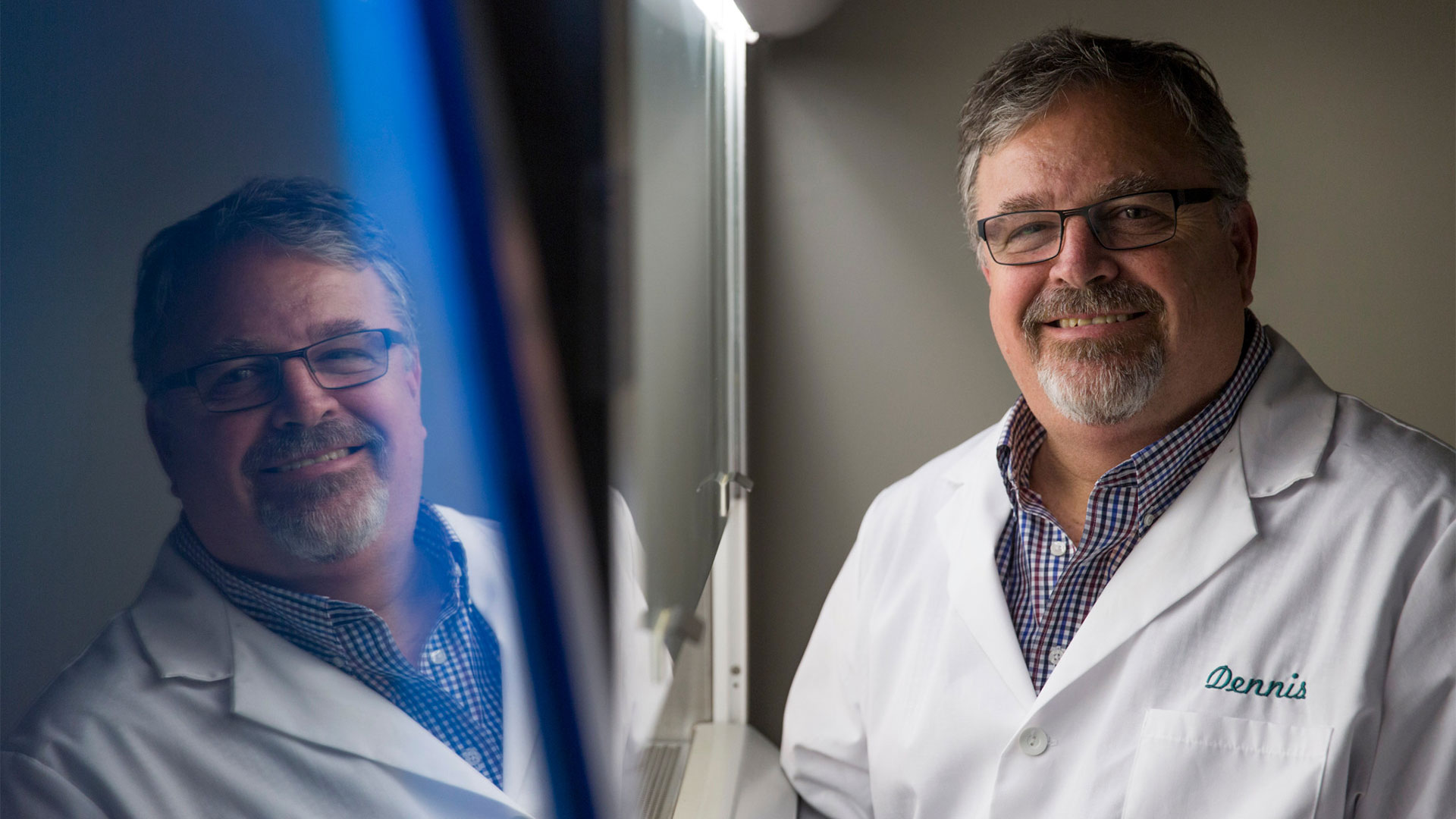

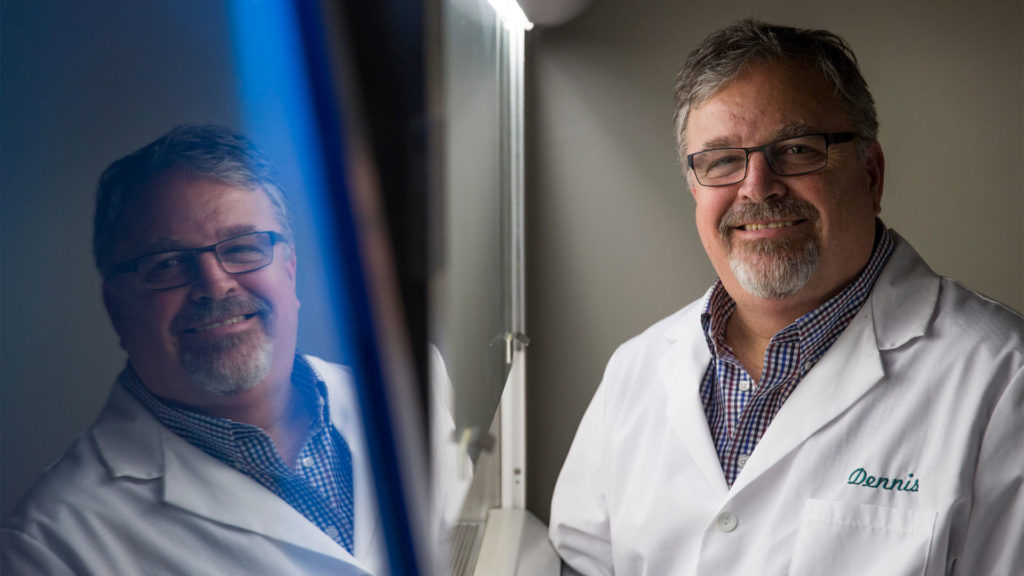

CTEGD Director Dennis Kyle, GRA Eminent Scholar Chair in Antiparasitic Drug Discovery and head of the Department of Cellular Biology, became fascinated with the Plasmodium parasite early in his career, spending time living in Thailand and working in refugee camps where malaria is prevalent.

“When I first got to the refugee camp and saw the situation people were living in, I questioned my decision to become a scientist in the lab instead of becoming a physician,” Kyle said, recalling a camp he worked in that housed about 1,300 kids between the ages of 2 and 15. “There was a guy who was a leader in the group who probably had no more than an early high school education. He said, ‘Look at what you can do—you might generate something that would benefit all of us. The physicians we have in the camp can only work on a few people at a time.’”

Kyle’s laboratory is looking to repurpose medications that have antimalarial properties, a safe way to reduce the development time from lab to clinical use. He’s optimistic we will see a drug treatment that eliminates vivax malaria.

“That’s where UGA is playing a major role,” he said. “The Gates Foundation funded us to develop tools to study the dormant parasite in the liver. And we’ve been successful.”

One of Kyle’s collaborators is Samarchith Kurup, assistant professor of cellular biology, who studies the human immune response to Plasmodium infection.

“We use mouse models to delve into the fundamental host-parasite interactions, which you cannot do practicallyin humans,” Kurup said. “Our understanding of these fundamental processes gives rise to newer and better vaccination approaches and drugs.”

Another important CTEGD addition is Chet Joyner, assistant professor of infectious diseases, whose work has helped make it easier to study dormant parasites stateside.

Like other Plasmodium researchers, Joyner became interested in parasites at an early age. During an undergraduate parasitology class, he discovered how little was known about P. vivax. He was already interested in how diseases develop, so for graduate school he focused on the liver stage of vivax malaria. However, it was a difficult task.

“At the time, the technologies weren’t there,” Joyner said. “Dennis was working on his system, but it wasn’t on the scene yet. I changed from studying the parasite to studying the animal model to understand pathogenesis and immunology in humans.”

Joyner joined UGA after completing his postdoctoral training at Emory University, where he developed a non-mouse animal model to study vivax malaria.

“We have to go to [Thailand] where people are infected and collect blood samples and then feed mosquitoes these samples to do the necessary studies,” Kyle said. “That’s been very impactful. We’ve gotten a lot of data out of it, and now with Chet’s model it all can be done under one roof.”

Joyner wants to understand the human immune response with a focus on vaccine development. Building on Muralidharan’s and other researchers’ findings of how the parasite interacts with the RBCs, Joyner’s vaccine program targets a specific protein in the parasite that inhibits the development of immunity.

“My colleagues have shown that if you knock this protein out in the parasite, the immune response in mice is actually great, and we are now working together to evaluate this in non-mouse models.” Joyner said.

Joyner also has collaborated with Belen Cassera, professor of biochemistry, to screen drug compounds. Cassera’s training focused on metabolism to find drug targets. She is particularly interested in how a drug functions.

“If we understand how the drug works, it will help us predict potential side effects in humans,” Cassera said. “We can’t predict everything, but knowing how it works gives you some confidence in whether it will work in humans.”

Cassera is focused on finding drugs that will treat the more lethal Plasmodium falciparum, the predominant species in Africa, which is rapidly becoming resistant to current treatments. Her work is complementary to Kyle’s.

“They run certain assays for the liver-stage infection, and our lab benefits because we want to know if the drug we are developing is specific for the blood stage or can tackle all stages,” Cassera said.

Don’t forget the mosquito

“Malaria is a vector-borne disease transmitted by a mosquito. You need to tackle not only the parasite in the human but also stop its transmission,” Cassera said. “CTEGD is unique because we can study the whole life cycle, including the mosquito.”

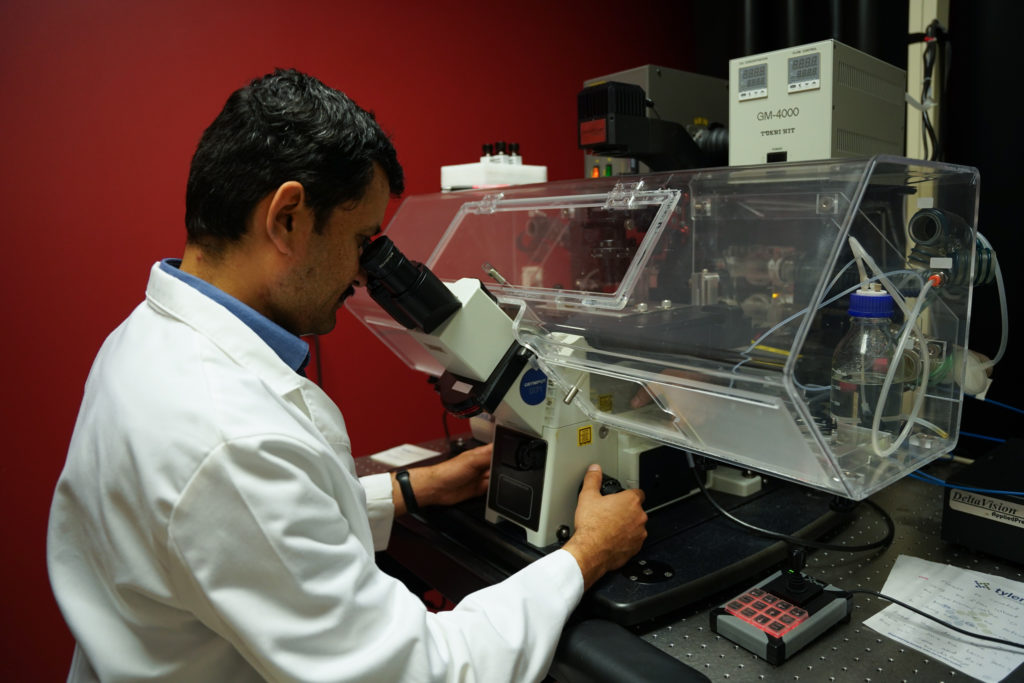

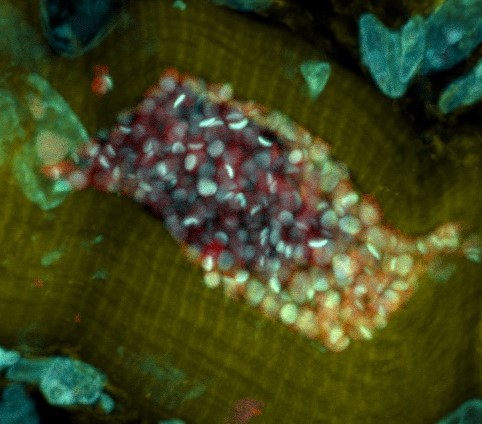

Michael Strand, H.M. Pulliam Chair of Entomology in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and a National Academy of Sciences Fellow, is an expert on parasite-host interactions. Instead of the human host, he is interested in mosquitoes. Recent work indicates blood feeding behavior of mosquitoes strongly affects malaria parasite development while the gut microbiota of mosquitos could lead to new ways to control populations. Having the SporoCore insectory on campus aids his research.

Established in 2020, SporoCore, under the management of Ash Pathak, assistant research scientist in the Department of Infectious Diseases, provides both uninfected and Plasmodium-infected Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes to researchers at UGA and other institutions. Like Joyner’s animal model, the insectory allows for research to be done in the U.S. that would otherwise require field work in an endemic country.

Old-school interventions like mosquito nets, combined with new drug therapies, have reduced the number of malaria deaths, which declined over the last 30 years before rising slightly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Great strides have been made to control and treat malaria—but not enough. New tools, like the ones being developed at CTEGD, are needed to keep pushing malaria’s morbidity and mortality rates in the right direction.

“The hard part—what can’t be done easily with the tools we already have—is being done,” Kyle said. “We just need new tools, which is one of the things that our center is really a leader in.”