UGA geneticist gets to take risks with new seed grant

By Donna Huber

Tania Rozario, assistant professor in the Department of Genetics and member of the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, recently received a seed grant from the Hypothesis Fund to develop a new approach toward advancing tapeworm research. Her natural inquisitiveness and willingness to tackle tough questions has led to this moment.

As a child in Malaysia Rozario was fascinated with the world around her. Her interest was fostered by her grandfather who was an amateur botanist and science teacher. After reading about NASA in a kid’s science magazine, she wrote a letter to them. Their willingness to engage with her inspired her to see science as a real career choice.

“I was exposed to science at an early age,” said Rozario. “But what had the biggest impact on my decision to become a scientist was doing undergraduate research.”

By the time she enrolled in graduate school at the University of Virginia, she knew she wanted to study regeneration. She focused on developmental biology and embryology as she needed a strong foundation in these disciplines to pursue her future research. She returned to regeneration during her post-doctoral training in the Newmark laboratory at the Morgridge Institute for Research. It was then that she started her work in tapeworm regeneration.

“I was drawn to the untapped potential in tapeworms to understand basic biological functions,” she said. “Tapeworms have a complex lifecycle and are difficult to study in the lab – so there’s a challenge there too.”

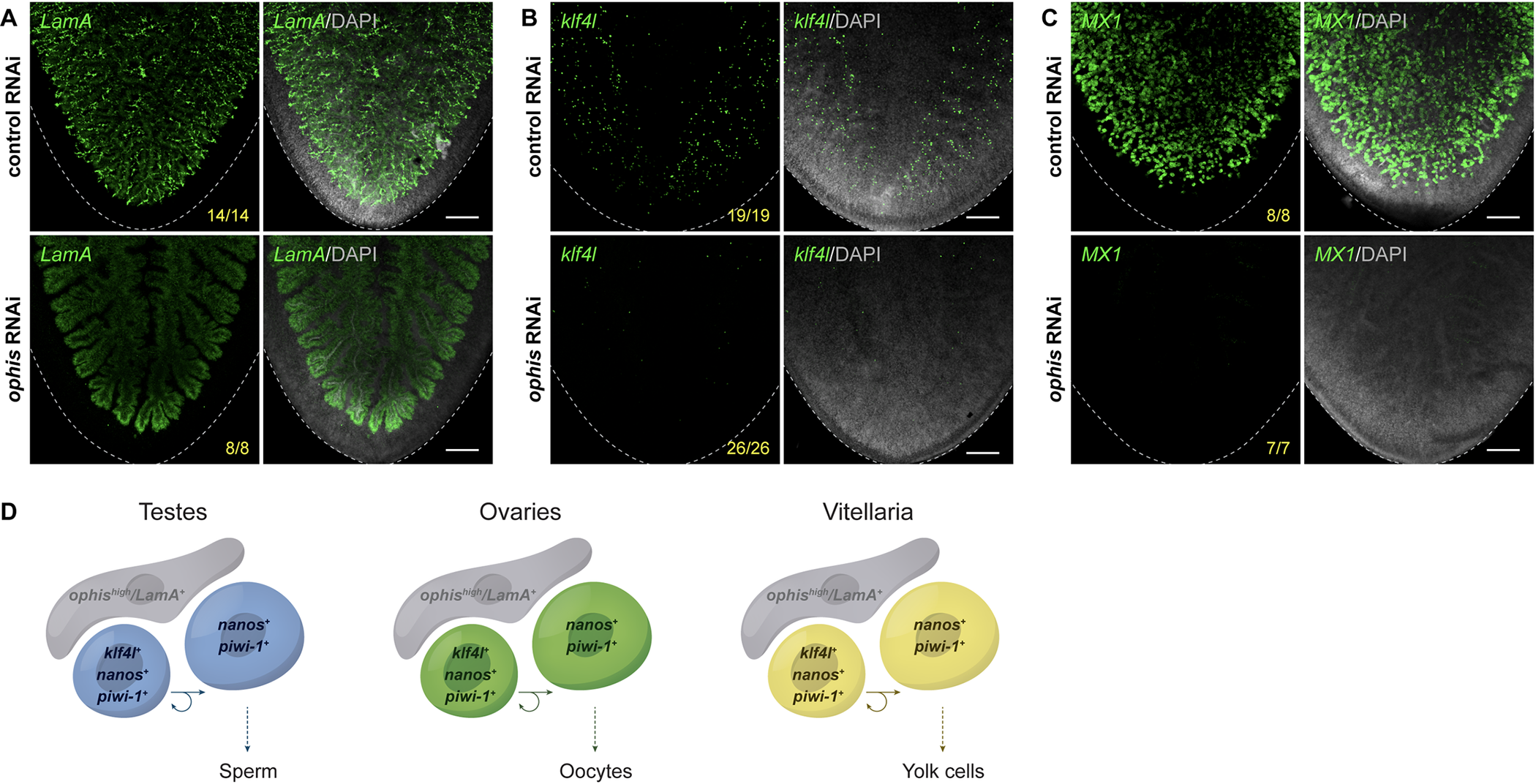

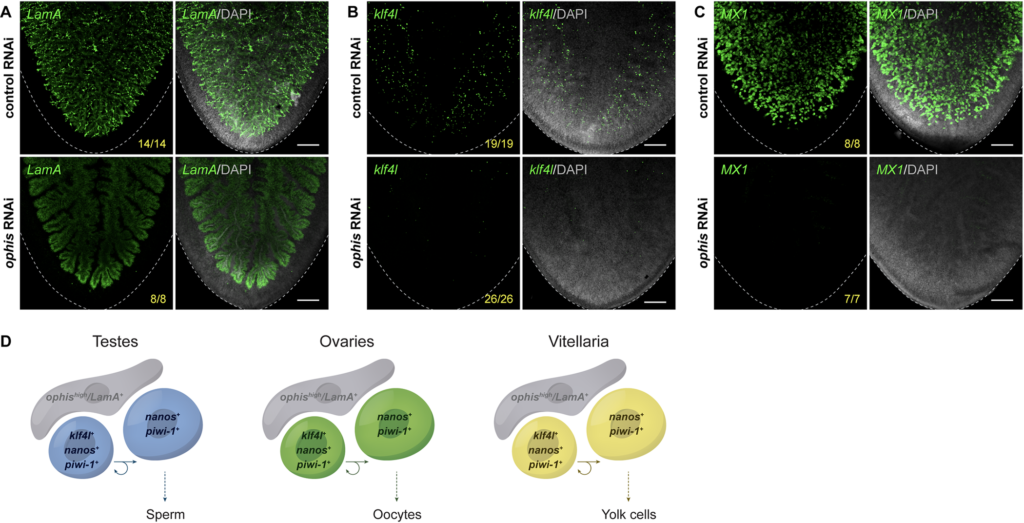

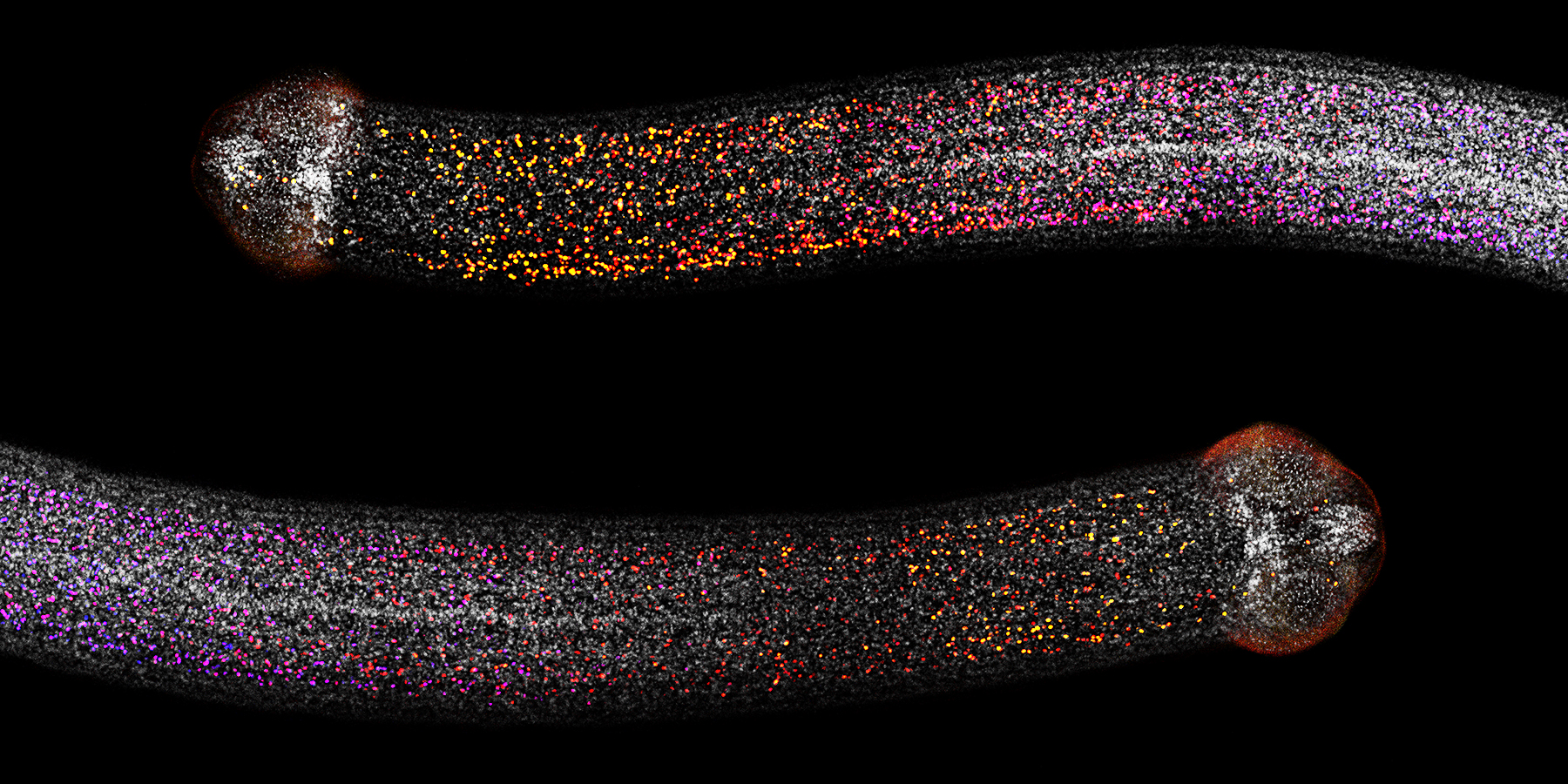

The mechanisms of regeneration are poorly understood in tapeworms. Stem cells are responsible for regeneration. The Rozario lab wants to know what is special about the stem cells and signals in the “neck” as this tissue is the only tissue capable of regenerating new segments, despite the fact that there are stem cells everywhere in the tapeworm body.

“Tapeworms can grow very large, but regeneration only happens from a tiny part,” explained Rozario. “We want to know what genes are controlling it but right now we don’t have sufficient tools.”

With the gene-editing tool CRISPR/Cas, researchers have been making remarkable strides in understanding genes in many organisms. However, there is no evidence that transgenesis, the process in which genes are inserted into an organism, works in tapeworms.

This is where the seed grant from the Hypothesis Fund comes in.

“They have scouts who are looking for unconventional science – research where although there may be risk or uncertainty that it will work, it could have a transformational effect if it does,” said Rozario.

The Hypothesis Fund provides seed grants for bold ideas at the earliest stage of research, often before any preliminary data have been generated.

“There are a number of barriers to getting CRISPR/Cas to work in an organism,” said Rozario in response to the risk of this project.

She lists three things that are needed to successfully use CRISPR/Cas: the right type of organism, access to an early development stage, and the expertise.

“We are in a good position to make this work,” further explained Rozario.

The Rozario lab has successfully developed a number of tools to better study the tapeworm in the lab. Since tapeworms produce both male and female gametes in every segment there is plenty of early development stage material to work with.

“Thanks to this gift, we are able to bring in post-doctoral researcher Olufemi Akinkuotu from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine,” said Rozario. “He has specific training in developing gene-editing tools in parasitic nematodes, which are distantly related to tapeworms but share many parallel challenges.”

While there is still a risk that CRISPR/Cas won’t work in tapeworms, if it does the payoff could be huge – not only for understanding the basic biology of tapeworms, but to further our understanding of stem cells in other organisms.

This story first appeared at https://research.uga.edu/news/uga-geneticist-gets-to-take-risks-with-new-seed-grant/