Daniel Colley: The Schisto Kid

By John H. Tibbetts

One day Daniel Colley raised his hand to volunteer, setting in motion five decades of scientific adventures. It was 1969, and Colley’s postdoctoral adviser, Byron Waksman, a renowned immunologist at Yale University School of Medicine, had stepped into the laboratory and asked if anyone wanted to go to Brazil.

“I have no idea why my hand shot up,” says Colley. “I didn’t know anything about Brazil. My wife and I didn’t even have passports. I asked Byron about the nature of the research, and he said, ‘Schistosomiasis.’ My response was, ‘What’s that?’”

Colley, today a UGA immunologist and Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, became fascinated by schistosomiasis, a parasitic worm infection plaguing poverty-stricken communities in sub-Saharan Africa and around the world. Globally more than 250 million people are infected via contact with water that carries the parasites.

The waterborne worms penetrate human skin and take up residence in blood vessels. About 5 to 10 percent of infections progress to life-threatening disease over decades. But most people experience more subtle symptoms such as fatigue, anemia, wasting, malnutrition and impaired cognitive development.

“Children playing in the water are picking up these chronic parasitic infections,” he says, “so they are sick and don’t do as well in school. If kids don’t receive what they need to develop early in life, it can become a lifelong disability.”

After his Brazil sojourn, Colley arrived at Vanderbilt University in 1971, setting up a lab and beginning his career-long effort to understand the immunological paradox of schistosomiasis (or “schisto,” in the vernacular).

“The more I learned about schisto, the more interesting it became,” says Colley, who tweets as @SchistoKid. “It has a bizarre life cycle. Here’s a worm that can live inside your blood vessels for up to 40 years, though more typically it lasts for five to 10 years. Why doesn’t your immune system get rid of this creature sooner? That was a very intriguing question.”

In infected human blood vessels, the female worms produce eggs that the male fertilizes. Many of the eggs escape the human body in urine or feces. When people urinate or defecate in or near fresh water, the eggs can infect freshwater snails, where the parasite develops and rapidly multiplies. When worms re-enter fresh water, they can find human victims.

Meanwhile, the body’s remaining worm eggs are swept by the bloodstream into the gut wall and the liver or bladder, where they become lodged. The immune system fights these egg intruders with a delicate, two-pronged effort: First, masses of cells called granulomas wall off the eggs, isolating them from surrounding tissue and reducing disease. But the immune system must also regulate granuloma growth. For most people, this regulatory response keeps granulomas relatively small, but some grow over decades, eventually causing fibrosis and blocking blood flow through the liver, causing internal bleeding.

“Schisto is a very complex puzzle for an immunologist,” Colley says. “If you fail to have the initial immune response against the egg, you die. But if you fail to regulate this immune response against the egg over time, you die. How our immune system has co-evolved with schisto is fascinating to me, and I still haven’t figured out how it’s done.”

In 1992, he joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a year later was promoted to director of its Division of Parasitic Diseases. “I learned about a lot of other parasitic diseases. It was an incredibly broadening experience that became useful in my later work at UGA. From my colleagues, I gained knowledge in epidemiology—the incidence and prevalence of diseases and detecting the sources and causes of epidemics.”

He arrived at UGA in 2001 as professor of microbiology and director of the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, created only three years before. “UGA started the center and took risks by investing in it,” he says. “Now it’s globally famous for its work in parasitic diseases and has 23 principal investigators.”

During the past decade, Colley has been director of UGA’s Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE), a program supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. SCORE scientists study strategies used in eight sub-Saharan African countries to control and eventually eliminate schistosomiasis. Today, most sub-Saharan African governments collaborate with the World Health Organization and a pharmaceutical company to provide a free drug, praziquantel, that treats existing infections and can significantly reduce new cases.

“SCORE has shown that mass interventions with praziquantel do work, and they are best done every year,” he says. SCORE researchers also helped develop a more rapid and precise diagnostic test for schistosomiasis, discovering many more cases in children than previously thought.

“The main message I’ve learned in my career is that diseases such as schisto are diseases of poverty,” he says. “Poverty contributes to these diseases, and poverty is also the result of them. If you are a stunted kid, and you have anemia, and your cognitive development is not great because of a parasite, it’s harder to succeed.

“People are the same everywhere—they all want a better life, and in some places, that’s not happening. Fighting these infections is an important part of making lives better.”

Help inspire future generations of researchers by supporting the Center for Tropical & Emerging Global Diseases

[button size=’large’ style=” text=’Give Online’ icon=” icon_color=’#b80d32′ link=’https://ctegd.uga.edu/give/’ target=’_self’ color=” hover_color=” border_color=” hover_border_color=” background_color=” hover_background_color=” font_style=” font_weight=” text_align=’center’ margin=”]

Originally published at UGA Research.

Grad school ready

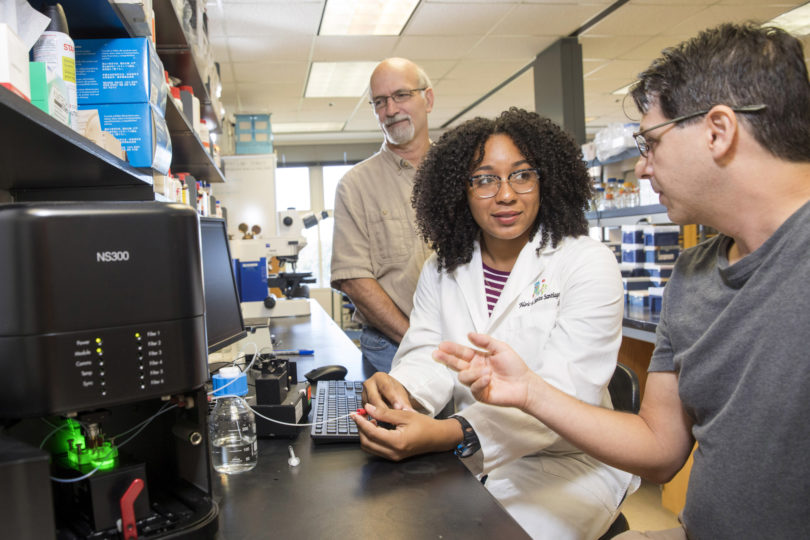

PREP@UGA Scholars program trains next generation of life sciences researchers.

As an undergraduate student in Maryland, Ian Liyayi planned to major in nursing but got lost on the campus tour and found himself in the biochemistry department. He liked that even better.

When it came to preparing for graduate school, Liyayi didn’t want to get lost along the way, so he applied for the University of Georgia’s competitive PREP@UGA Scholars program to give him more experience before he began applying to doctoral programs.

“This program gets you fully ready for grad school because you get a ton of time in the lab,” said Liyayi, a current scholar who said he enjoyed research experiences in his undergraduate years at Stevenson University but didn’t gain much hands-on laboratory experience on long-term projects.

“I knew I wanted to do graduate school, but I didn’t feel like I was completely ready,” said Liyayi, a native of Kenya who grew up in Baltimore. “This program seemed like a perfect fit.”

With funding from a National Institutes of Health grant, the PREP@UGA Scholars program was created five years ago. Earlier this year, co-directors Erin Dolan and Mark Tompkins received a $2.1 million, five-year grant renewal, which will continue to fund a cohort each year of six to eight scholars from underrepresented groups or with limited opportunities in the STEM fields at their undergraduate institution.

To date, 32 students have participated in the program. About one in four later enrolled in a UGA doctoral program, with the remainder going on to graduate programs at other institutions. Programs such as PREP@UGA have helped make UGA the nation’s top public flagship university for the number of doctoral degrees it awards to African Americans.

“Undergraduate students are in the mindset of taking classes, but in grad school they don’t just consume knowledge, they create it,” said Dolan, Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Innovative Science Education in the department of biochemistry and molecular biology, part of the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “This program smooths that transition to graduate school and to thinking like a scientist.”

While students spend most of their time in a laboratory, they also go through professional development workshops and benefit from the advice of a faculty mentor and an advanced graduate student or postdoctoral mentor. “It’s a holistic program,” Dolan said. “We focus on the research experience and the career around it.”

For Jilarie Santos Santiago, those mentors have helped her realize her potential in just her first few weeks on campus. “I am stepping out of my comfort zone,” said the graduate of the University of Puerto Rico Humacao, who is currently conducting research in Stephen Hajduk’s lab.

As an undergraduate, Santos Santiago worked on a project for several years to determine a way to thwart parasitic nematodes from destroying the plantain harvest on her home island, but she wanted to explore other areas of life sciences research and learn new techniques before beginning a doctoral program. She also wanted to improve her communication skills, and she’s excited to learn more about the process of publishing research articles.

“The transition to a Ph.D. program, it can be overwhelming. Even this building is confusing when you come from a small college,” Santos Santiago said from her lab in the Davison Life Sciences Complex. “It can be a lot to take in, but if you don’t take the first step, you never do it. This was the right first step for me.”

Tompkins, a professor of infectious diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine, said his experience as a mentor for a PREP@UGA Scholar last year drove home the impact of the program on students, the research team and on academia as a whole.

“It’s a win-win for the students, the faculty member and the research mentor,” he said. “The perspectives that the scholars bring add a richness to the lab. For the university and academia, the program will have an intangible impact on increasing diversity in the long run.”

Tompkins’ former scholar, Carlie Neiswanger, who has recently begun her doctoral program in pharmacology at the University of Washington, said her experience as a PREP@UGA Scholar was “nothing short of life-changing.”

After a rocky start to her undergraduate education, she found her passion as a returning student but didn’t believe she had the grades and test scores to make graduate school an option. But her postbaccalaureate experience changed that while providing lessons in independent thinking and problem solving that have given her confidence going into her doctoral program.

“I knew that I wanted to stay in research after graduation, but I was at a loss for what the next steps would be if I wasn’t prepared for graduate school. The PREP program was a near-perfect solution for me,” said Neiswanger, an alumna of Washington State University. “Not only did I get to experience what it means to work full time in a lab while learning to balance things like classes and social life, it truly made me feel prepared for graduate work. … I worked really, really hard, and it paid off. Now I’m ready for the next step.”

First published at https://news.uga.edu/grad-school-ready/

Data boost: Using big data to fight disease

From leisure to health, digital databases can streamline nearly every facet of modern life.

Remember when making travel plans to a single destination took hours? Now booking flights, hotels and rental cars is just a few clicks—and a credit card—away thanks to travel sites like Expedia, Travelocity and others. Travelers get to compare competitors on price, amenities, customer reviews and proximity to popular locations. The sites pull together multiple data points from various sources (such as pricing from the seller, reviews from users, and maps from Google) and organize them for customers to view.

Jessica Kissinger, the director of UGA’s Institute for Bioinformatics and member of the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, is doing for infectious disease research what travel sites did for vacation planning.

All over the world, researchers are racing to stop the spread of deadly and debilitating pathogens such as malaria. As those researchers and public health officials determine, or record data about a disease, Kissinger and her colleagues work to make that data accessible and searchable by the global research community for free.

“We take data generated by others and make them better,” says Kissinger, a Distinguished Research Professor of Genetics. More specifically, Kissinger and a team of cell biologists, geneticists and computer scientists pull disease data from a variety of sources, translate them into standard formats and make them searchable.

Jessica Kissinger, the director of UGA’s Institute for Bioinformatics, is doing for infectious disease research what travel sites did for vacation planning.

Enabling Discovery

How does building a database fight disease? Data help researchers construct and test their ideas about how to create treatments for diseases or map out ways to halt their spread.

“We don’t give them answers,” Kissinger says. “We give them a framework in which to generate and test hypotheses.”

Kissinger and her team have built databases to take on malaria and other infectious diseases such as toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis and trypanosomiasis. They are also creating tools for studying childhood malnutrition and factors related to disease, and making them accessible to all as they become publicly available. These databases collectively service more than 70,000 unique users a month from more than 100 countries.

To put it simply, her work saves time. It speeds the pace discovery for the next possible solution, the next cure. Without these databases, researchers could spend weeks, months, even years researching existing literature on a disease in the library or recreating work in the lab.

These are tools by biologist for biologists … I think it is that sense of being a member of that community, having your finger on the pulse of what’s going on, that allows you to keep the tools useful. ~ Jessie Kissinger Director, Institute of Bioinformatics

Career Evolution

Kissinger didn’t set out to build databases.

She was trained as a molecular evolutionary biologist, not a computer scientist. “I like to see how molecules change over time,” she says. “When I started in school it was about how a gene or protein evolved.”

It turned out that her field was evolving too. Technology was allowing researchers to understand molecules through bigger data sets. Now, scientists aren’t just looking at individual genes but entire genomes, which are the complete sets of genes in a cell or organism.

As the field evolved, Kissinger learned and embraced the technology. Over time, she shifted her balance away from the so called “wet lab,” where she worked directly with the organisms, to focus mostly on the computer-based “dry lab.”

Her database work started with malaria and continued to expand.

“Now we make 10 different component databases for over 300 organisms (EuPathDB.org), a comparative database to see how conserved genes are across organisms and a new epidemiology database to study the prevalence, spread and factors related to disease in humans (ClinEpiDB.org).” she says.

Kissinger’s team relies on an expert advisory board that helps the researchers customize the databases for each disease community, so they have the largest impact on research. It helps that Kissinger started in a wet lab before diving into informatics.

“These are tools by biologist for biologists,” she says. “We have a lot of computer scientists in the middle, but I think it is that sense of being a member of that community, having your finger on the pulse of what’s going on, that allows you to keep the tools useful.”

SUPPORT OUR RESEARCH

Give to the Center Tropical & Emerging Global Diseases General Fund

[button size=’large’ style=” text=’Give Now’ icon=” icon_color=” link=’https://ctegd.uga.edu/give/’ target=’_self’ color=” hover_color=” border_color=” hover_border_color=” background_color=’#b80d32′ hover_background_color=” font_style=” font_weight=” text_align=’center’ margin=”]

Originally published at https://greatcommitments.uga.edu/story/data-boost/

Trainee Spotlight: Stephen Vella

Stephen Vella is a Ph.D. trainee in Silvia Moreno’s laboratory. He is originally from Indiana where he received his B.S. in microbiology at Indiana University. In his first year at UGA, he was awarded an Excellence in Graduate Recruitment Award and a Provost’s Scholars of Excellence Award Fellowship. He has also been awarded an Outstanding Poster Presentation at the Molecular Parasitology Meeting in 2016. And in 2017, he was awarded a T32 fellowship from CTEGD.

Faculty search underway for Assistant Professor

The Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences in the College of Pharmacy and the Center for Tropical & Emerging Global Diseases at the University of Georgia invites applications for a full-time tenure track position at the level of Assistant Professor.

We seek an individual who will build and maintain a strong extramurally-funded research program focused on parasites that applies cutting-edge approaches in chemical biology, molecular pharmacology, medicinal chemistry, or drug discovery. The successful candidate would build on the research strengths of the Department and the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, one of the world’s leading centers for parasite research. A commitment to excellence in teaching at the undergraduate and graduate levels within the College of Pharmacy is also required. The position includes a very competitive salary, excellent laboratory space, and a generous start-up package. Applicants must hold a Ph.D. (or MD) degree in a biomedical, biological, or pharmacological science, have at least two years of postdoctoral training and a strong publication record.

Applicants should submit a cover letter, curriculum vitae, research statement (up to 3 pages) and teaching philosophy. Three confidential letters of recommendation are required, and applicants should provide email addresses for referees in their application. Application materials submitted in other ways will not be accepted. Review of applications will begin on November 15, 2018, and continue until the position is filled. Contact pbsearch@uga.edu with questions.

The College of Pharmacy and the University of Georgia is committed to increasing the diversity of its faculty and students, and sustaining a work and learning environment that is inclusive. The University of Georgia is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, gender identity, sexual orientation or protected veteran status. Persons needing accommodations or assistance with the accessibility of materials related to this search are encouraged to contact Central HR (facultyjobs@uga.edu). Please do not contact the department or search committee with such requests.

Minimum Qualifications: Applicants must hold a Ph.D. (or MD) degree in a biomedical or biological science, and have at least two years of postdoctoral training.

Applications will be accepted until December 16, 2018.

[button size=’large’ style=” text=’Apply Now’ icon=” icon_color=’#cf0404′ link=’https://www.ugajobsearch.com/postings/33146′ target=’_self’ color=” hover_color=” border_color=” hover_border_color=” background_color=” hover_background_color=” font_style=” font_weight=” text_align=’center’ margin=”]